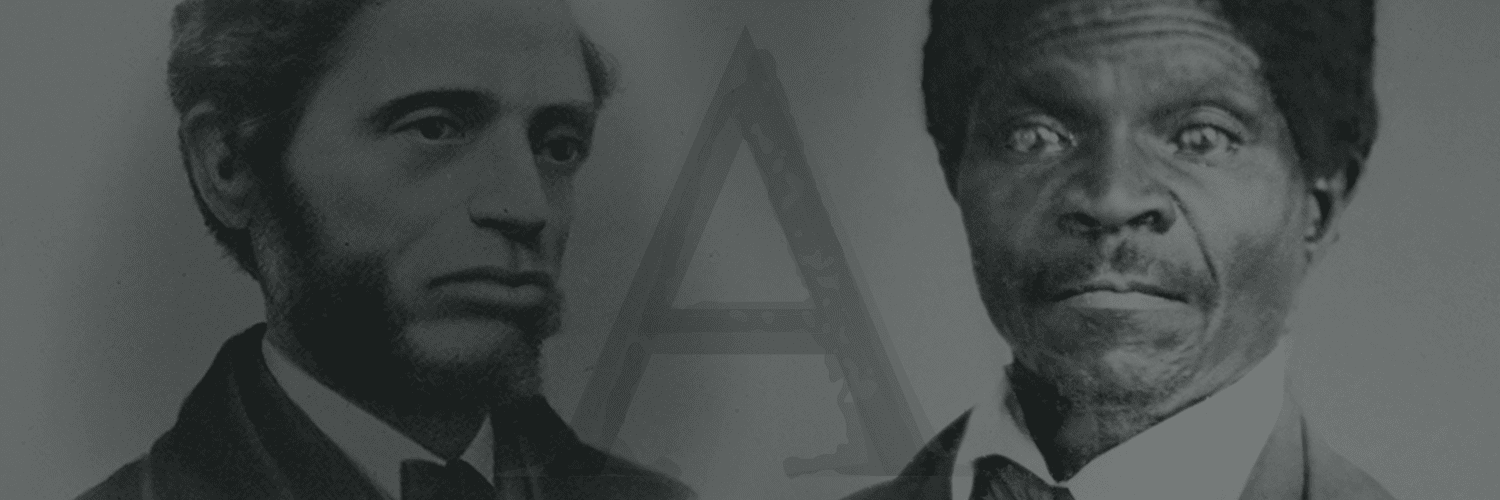

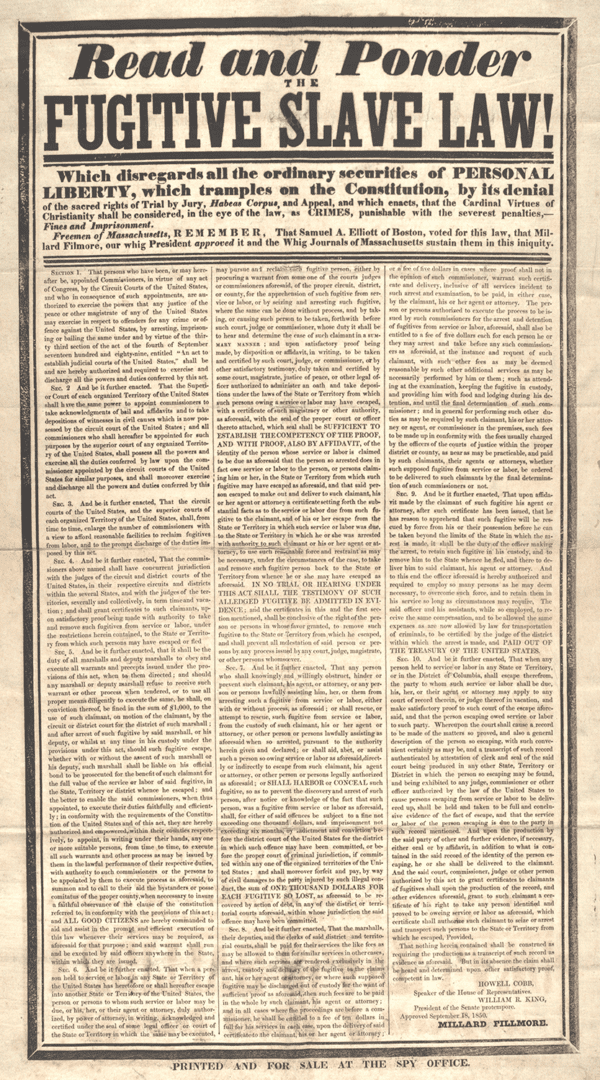

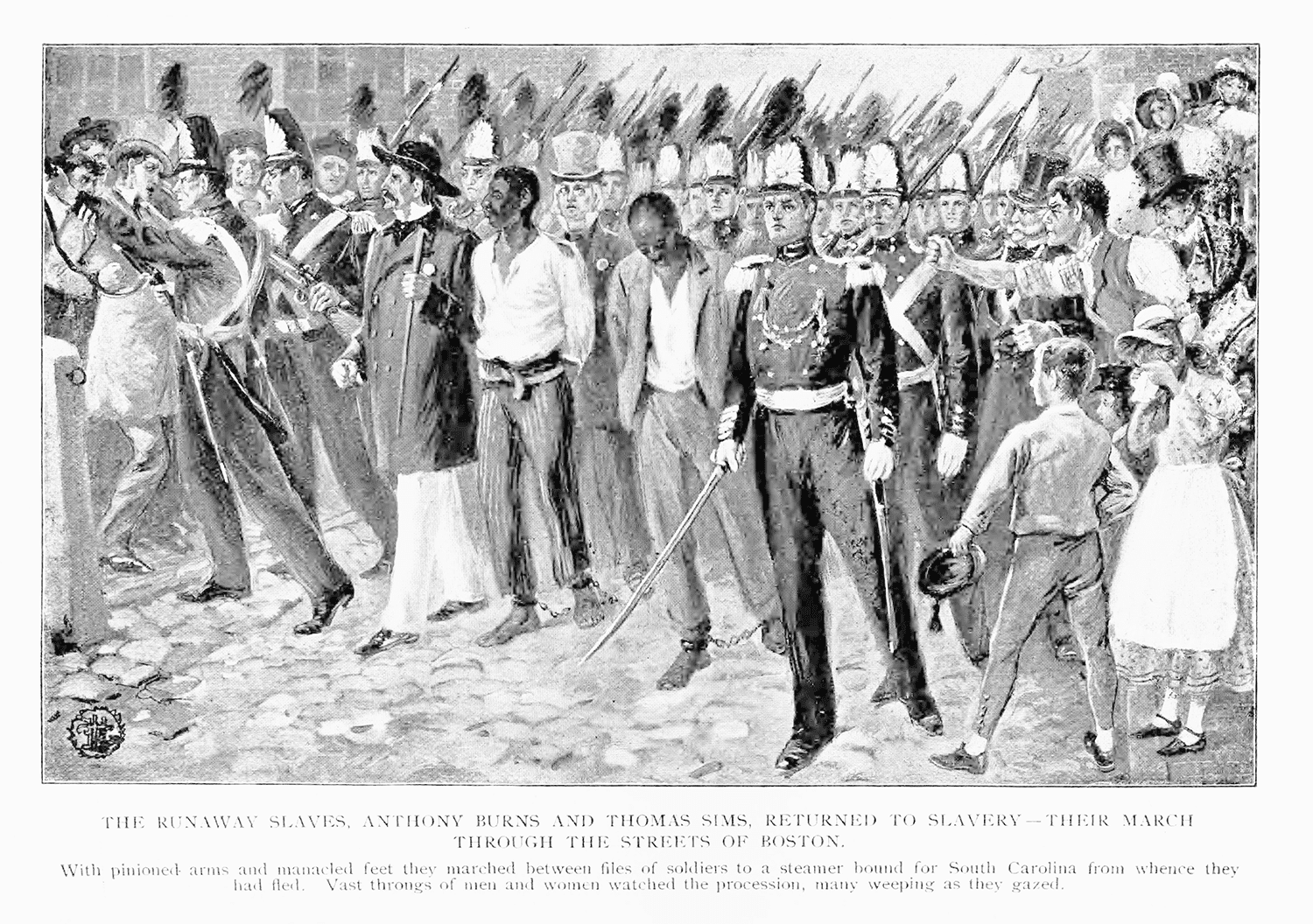

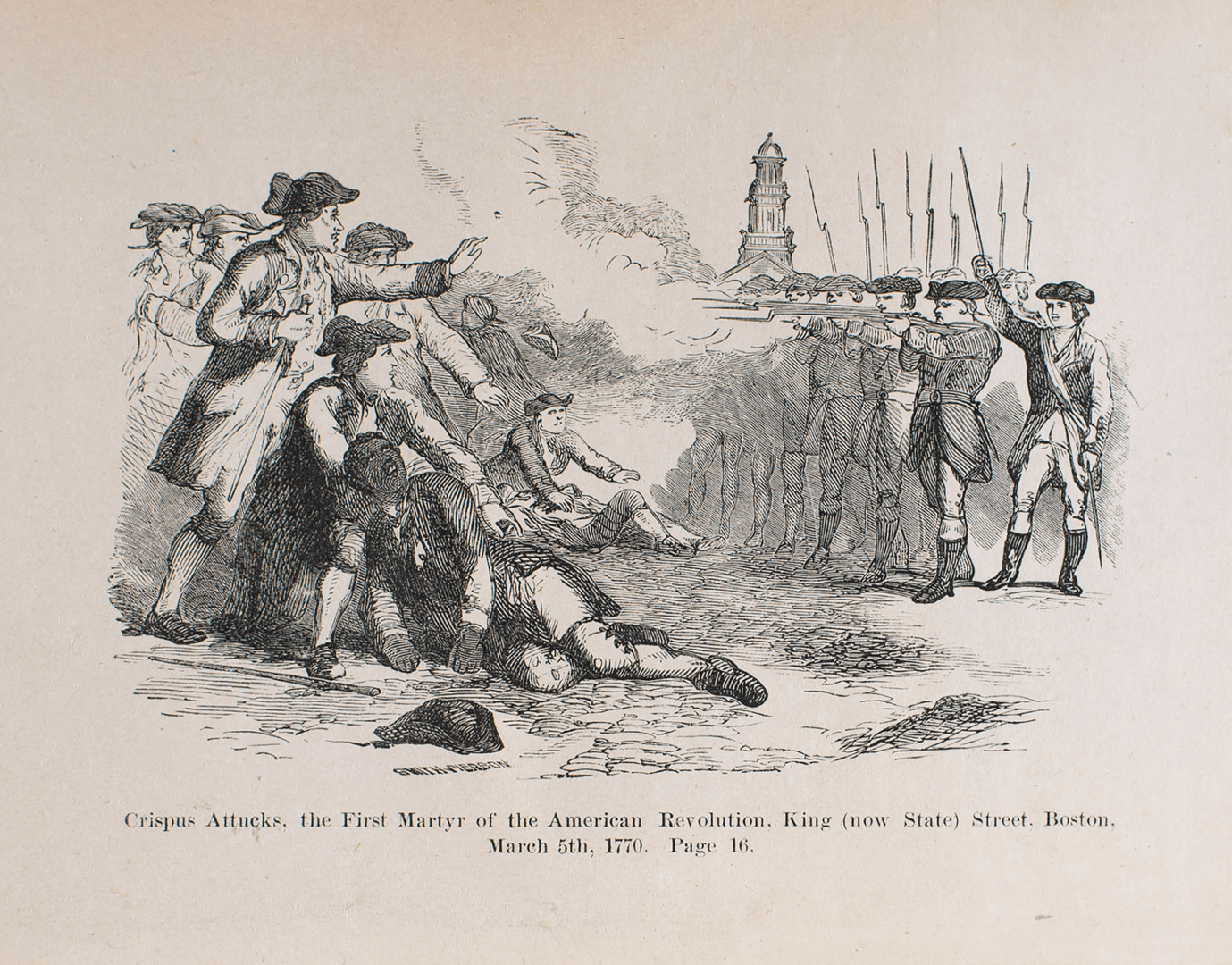

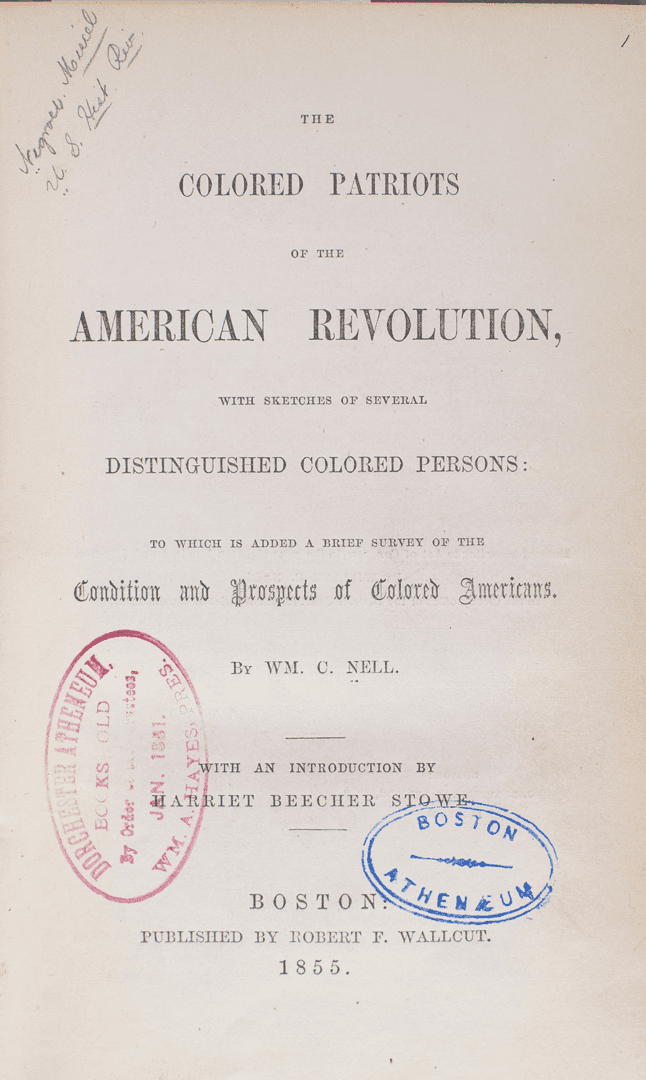

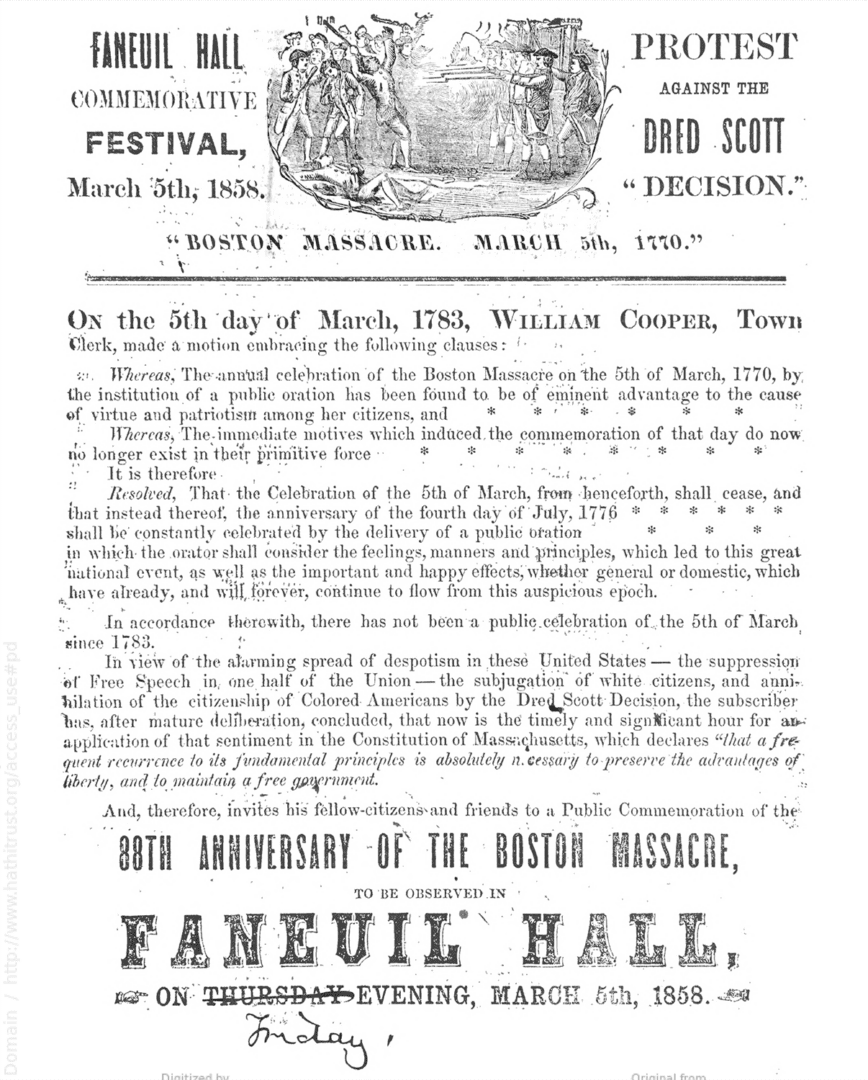

William Cooper Nell (1816-1874) was an abolitionist who challenged ideas about black racial inferiority by writing about and celebrating black achievement. His work was a response to those who defended slavery by arguing that blacks were incapable of citizenship. In his 1855 book Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, Nell made the case for African American equality by describing their contributions to the national struggle for freedom. A powerful passage in the book describes Anthony Burns walking through Boston to his re-enslavement in Virginia on a route that passes the spot where Attucks died for liberty.

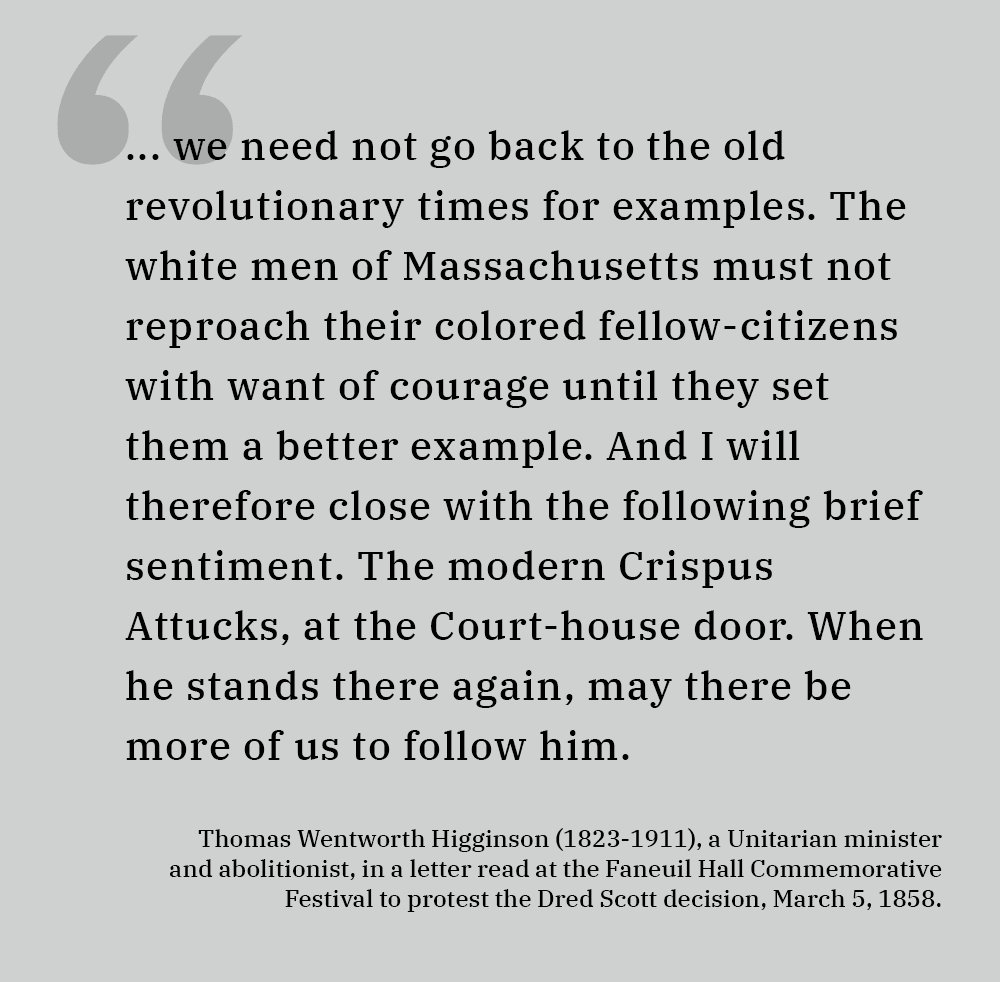

Nell’s book influenced abolitionists, including Lewis Hayden (1811-1889) and Frederick Douglass (1818-1895). When the Civil War began, Hayden and Douglass wanted black men to serve in the Union Army despite restrictions on their enlistment. They referenced Nell’s history, including his comments on Attucks, as they rallied the black community around the Union cause. By the time Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, African Americans across the country, inspired in part by these references to Attucks, enlisted in Massachusetts’ famed 54th Regiment. Nell watched the black troops depart for South Carolina from the site of Attucks’s fall in the Boston Massacre.