Fighting For Equity

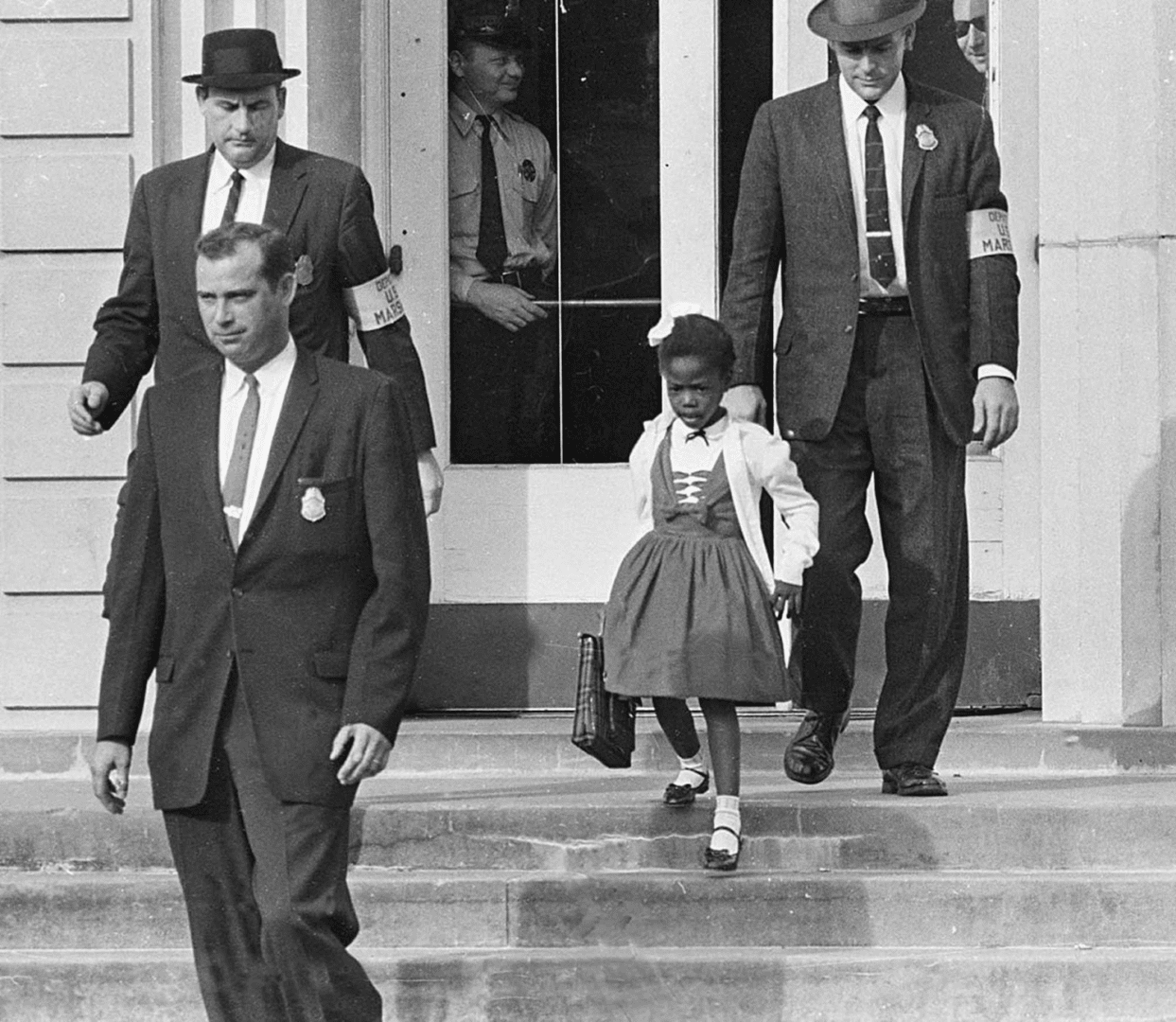

African Americans saw some progress in their fight for equality as courts began to rule against segregation, and elected representatives passed new civil rights laws in the second half of the 20th century. However, whites often resisted these changes with violence and intimidation. In Boston, Melnea Cass (1896-1978) resurrected Attucks Day in the 1970s to connect Attucks’s sacrifice to African Americans’ contemporary fight against inequality. Attucks Day became a powerful platform for Blacks to stake their claims for dignity and opportunity in the face of white backlash around school desegregation in the city.

Digital Exclusive

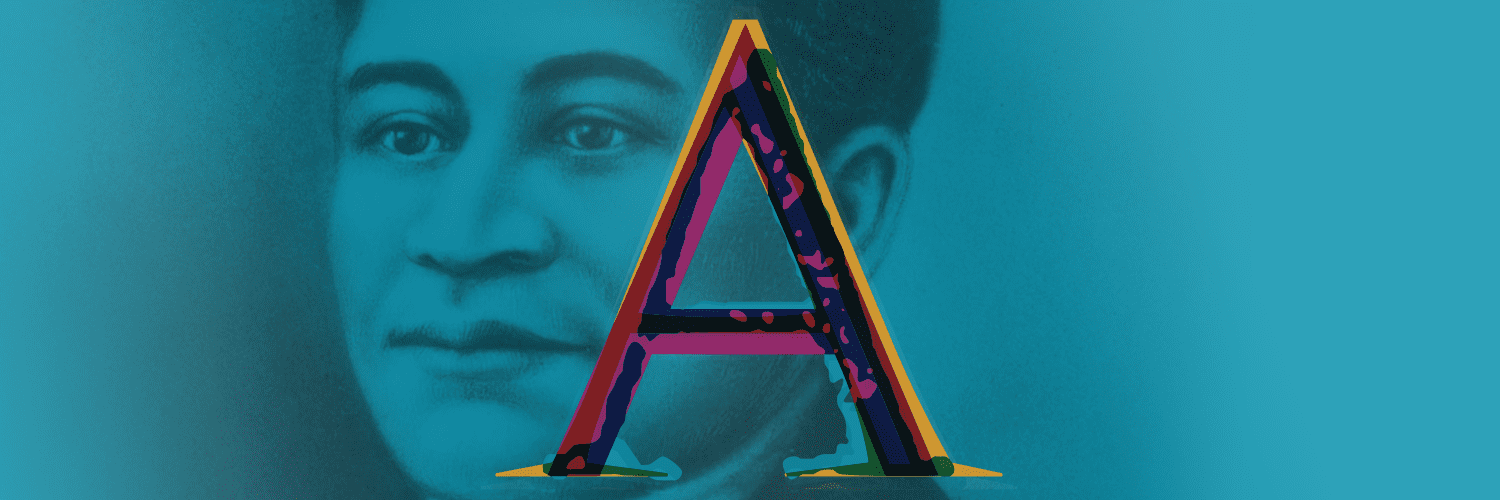

PORTRAIT OF MELNEA AGNES CASS

Photographer unknown

Undated

Photograph

Reproduction courtesy of Northeastern University Library

Click for larger image.

Melnea Cass (1896-1978) was a prominent civil rights activist in Boston. Her work was inspired by Rosa Brown, her mother-in-law and a civic organizer. As a young woman during the 1920s, Cass was an active member of the National Equal Rights League (NERL) and participated in many protests organized by William Monroe Trotter. Cass eventually became president of NERL and collaborated with others in the 1960s and 1970s to fight employment discrimination, unfair housing policy, and school segregation. Boston celebrates Melnea Cass Day on May 22nd.