Fighting For Equality

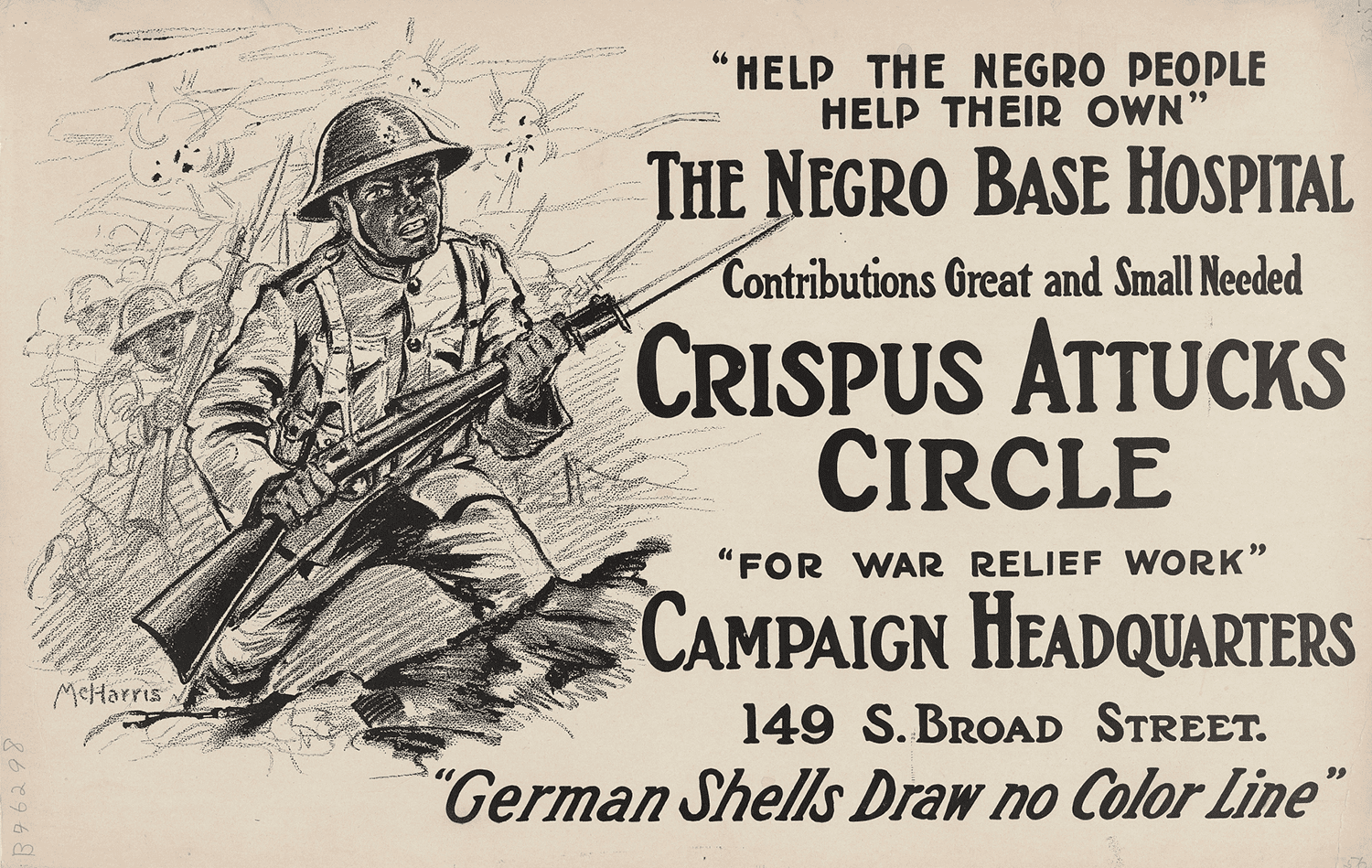

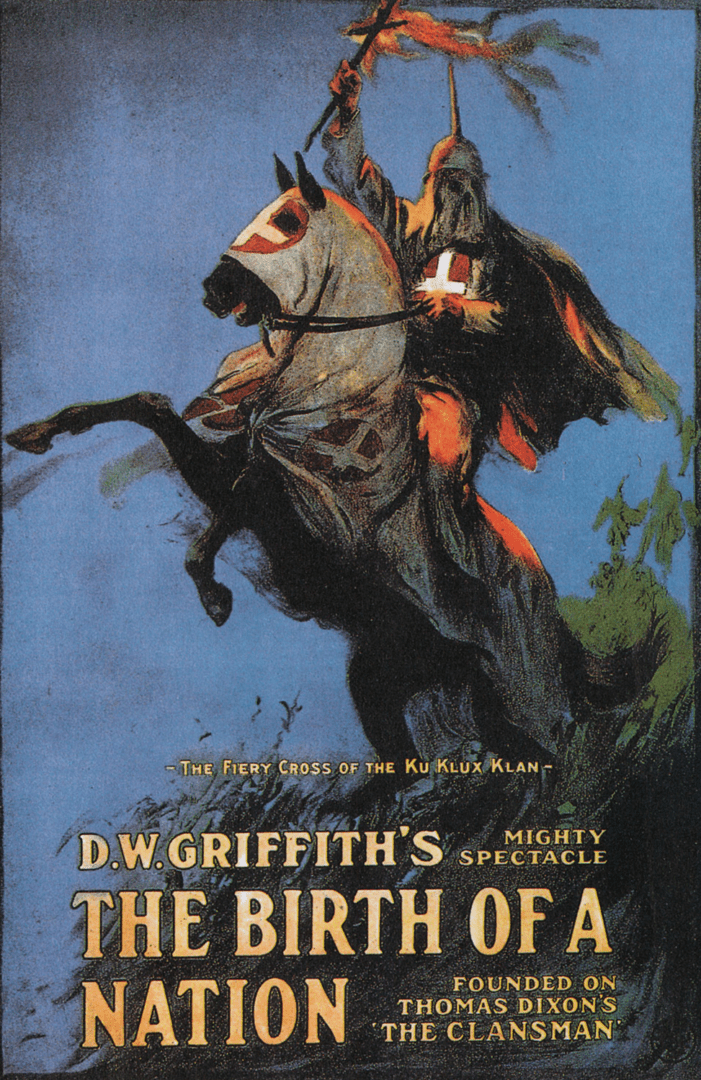

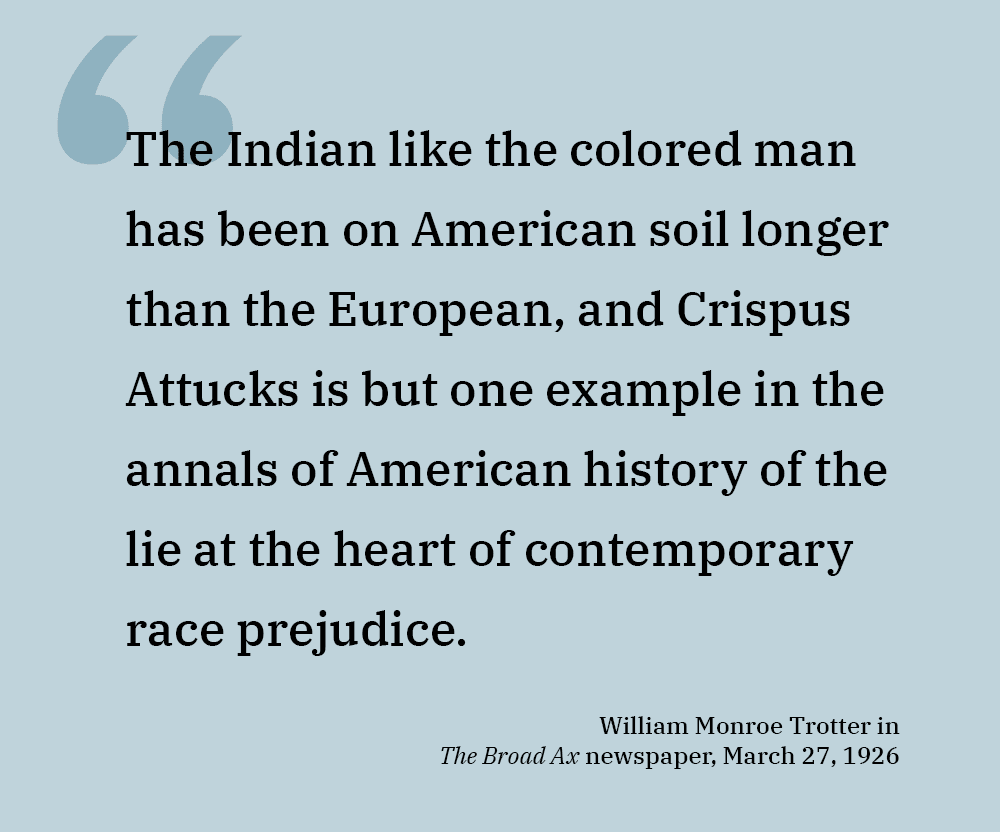

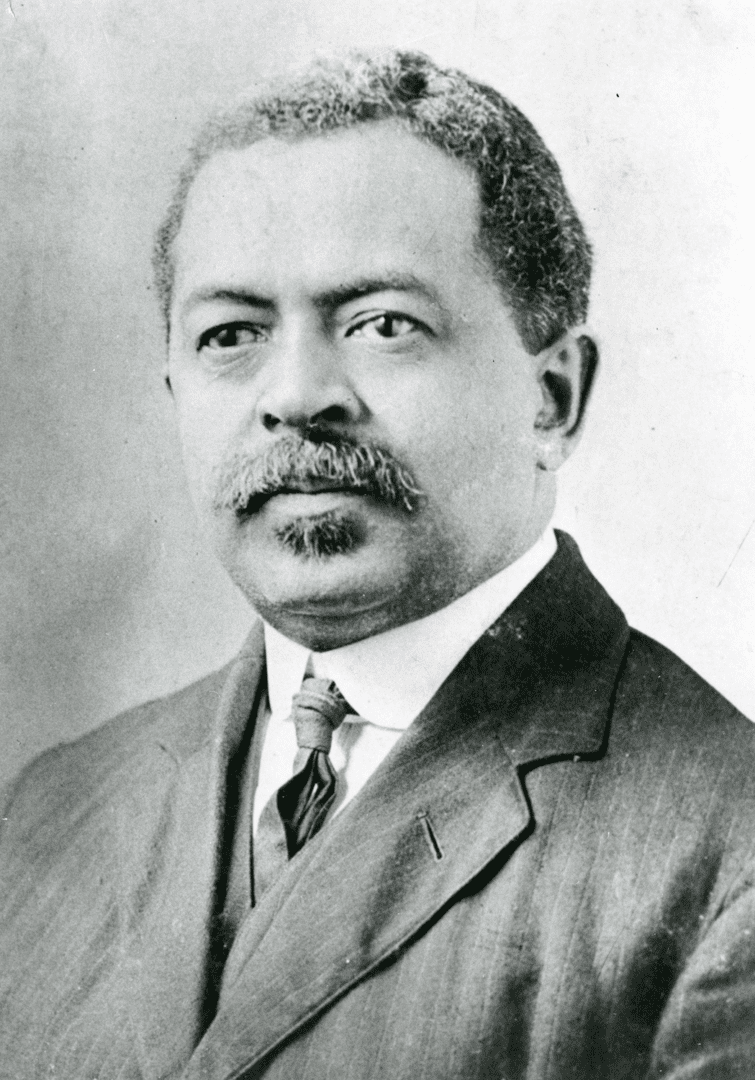

At the turn of the 20th century, white supremacists terrorized Blacks through lynching and expanded efforts to segregate them and deny them of their rights as American citizens. The child of abolitionists, activist William Monroe Trotter (1872-1934) invoked Crispus Attucks’s contributions to the nation’s founding to challenge whites who said Blacks were racially inferior and did not belong to the American story. Trotter inspired a new generation of African Americans to take a more confrontational approach in their fight for equality.

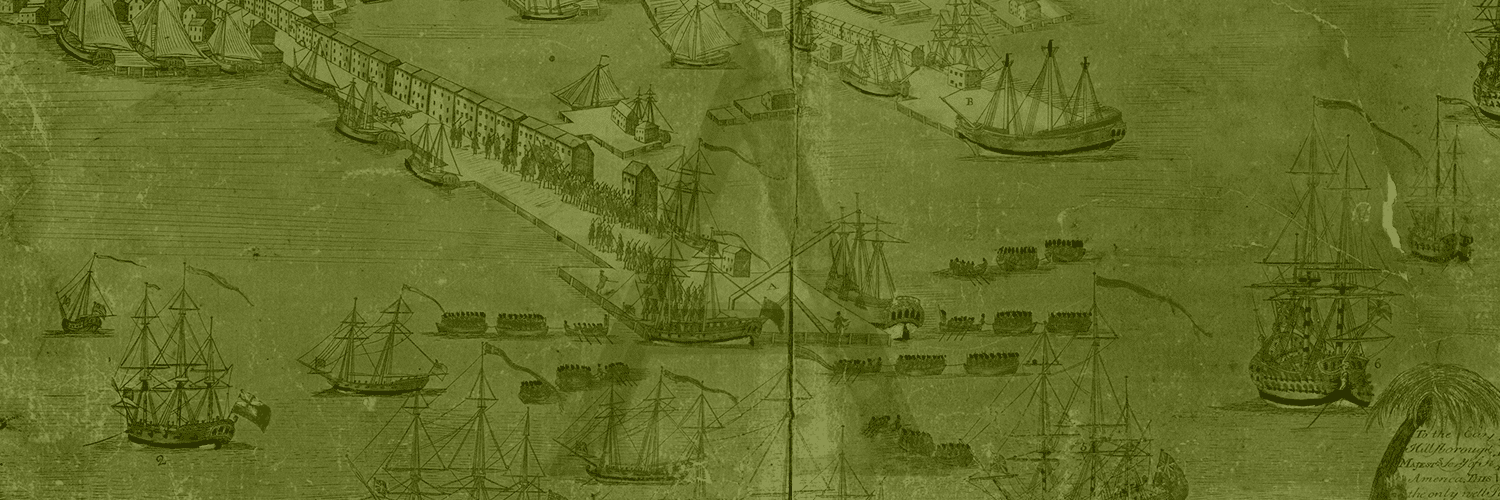

SILENT PARADE IN NEW YORK CITY AGAINST THE EAST ST. LOUIS RIOTS

Photographer unknown

July 28, 1917

Photograph

Reproduction courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Click for larger image.

In the early part of the 20th century, tens of thousands of African Americans fled north to escape poor economic conditions and racist Jim Crow laws in what became known as the Great Migration. In the summer of 1917, the Aluminum Ore Company in East St. Louis hired hundreds of Black workers to replace striking whites, igniting racial tensions and violence against African Americans in May. Tensions mounted until July 1-2, as white residents launched an attack on the Black community, with little to no intercession from local authorities. White rioters killed dozens of Black people indiscriminately, and burned down Black residences leaving thousands homeless. In response, the NAACP called for a silent protest parade in New York City to protest the violence. On July 28, 1917, nearly 10,000 Black men, women and children paraded in silence down Fifth Avenue. Marching to a beat of a drum, the demonstrators held picket signs demanding an end to racial injustice.