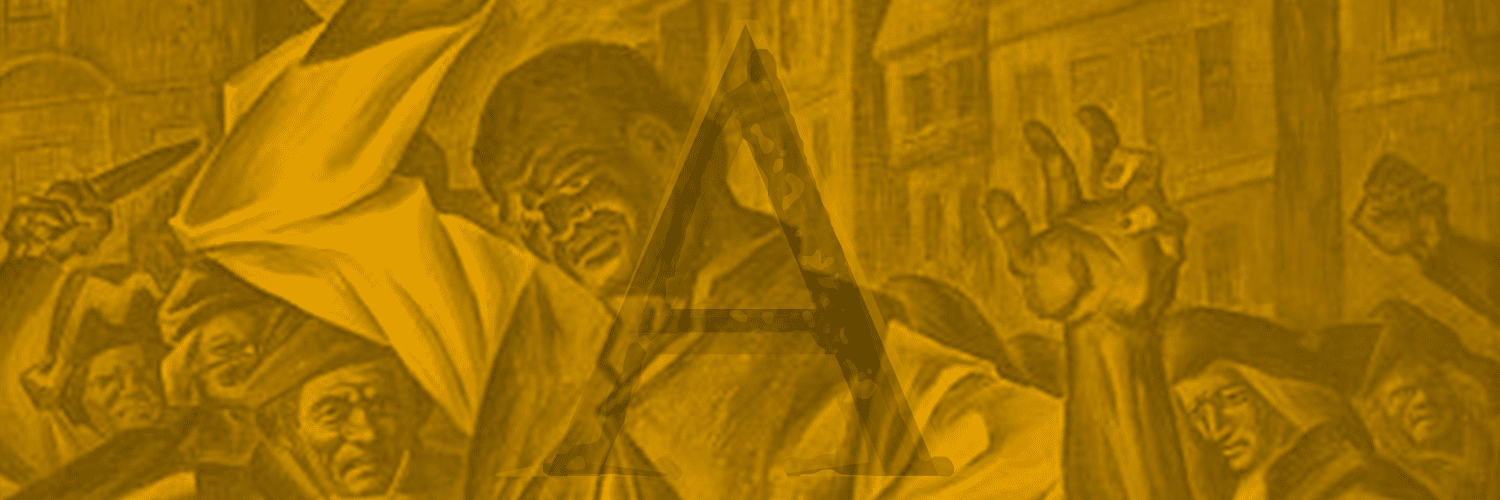

Fighting for Independence

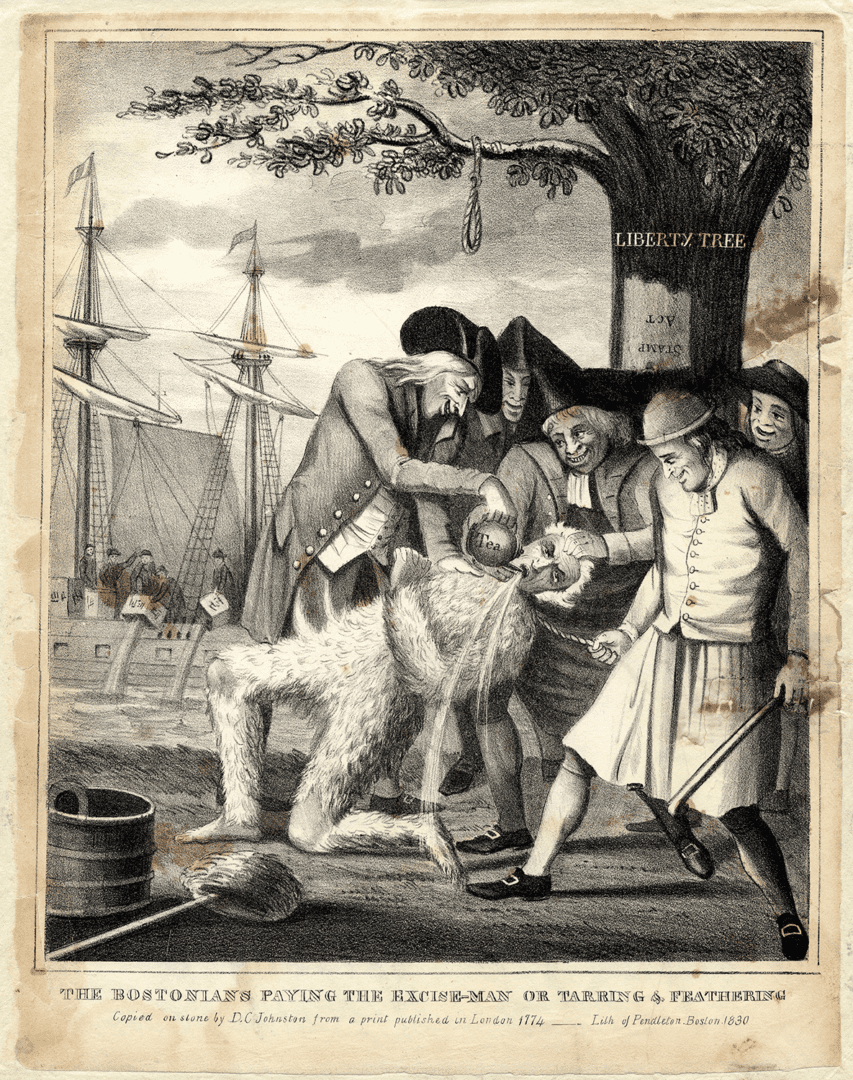

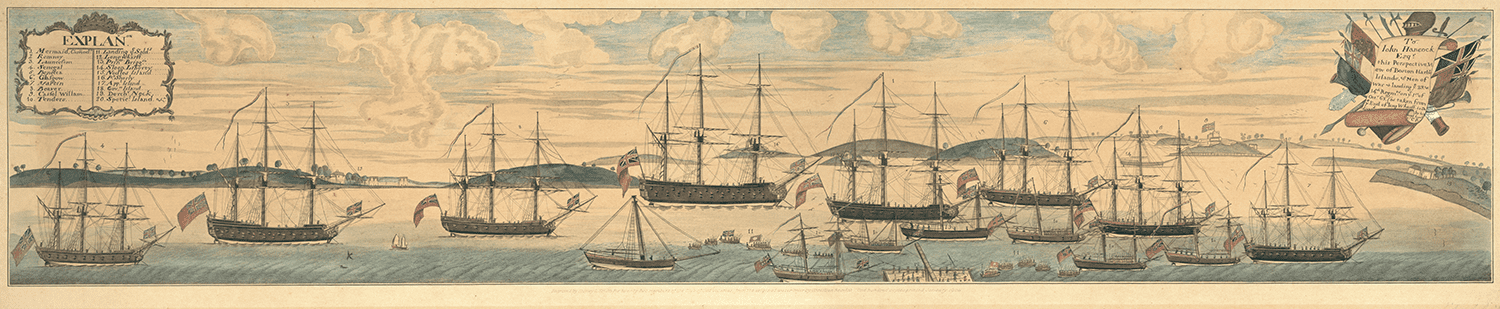

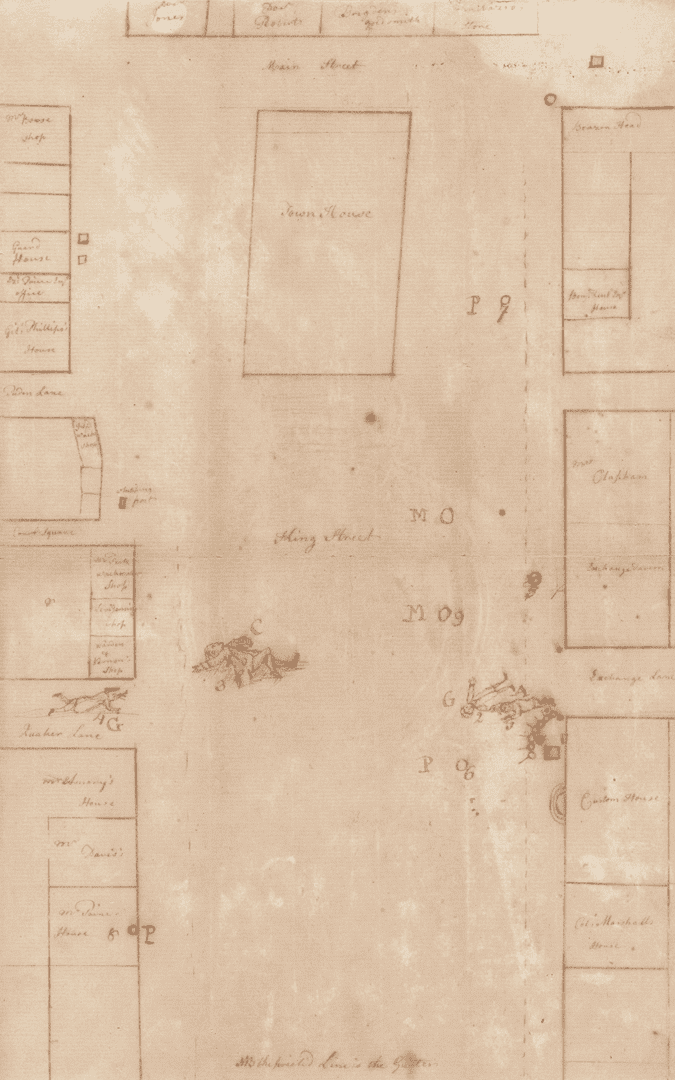

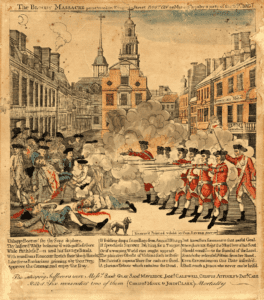

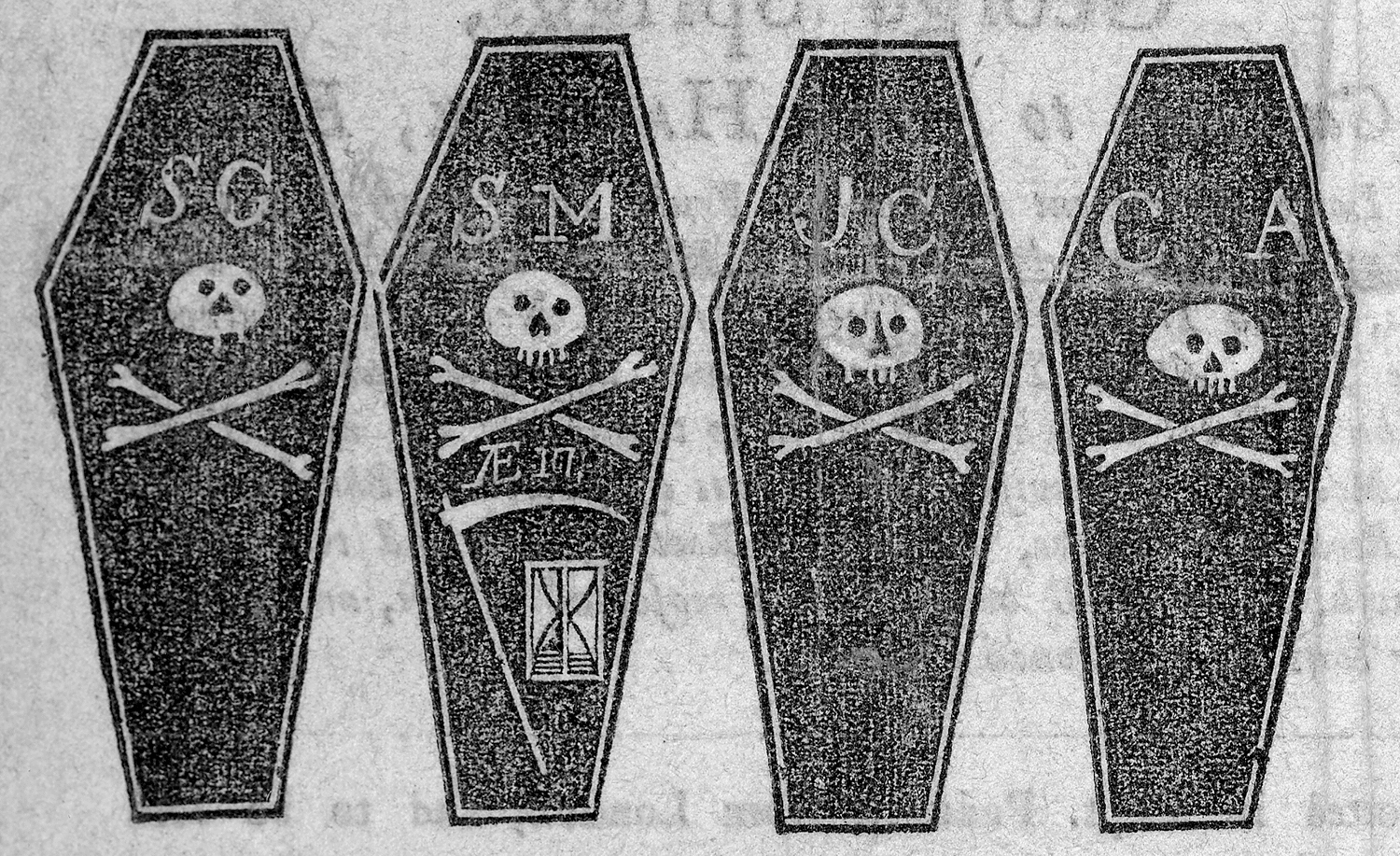

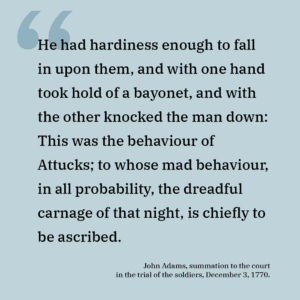

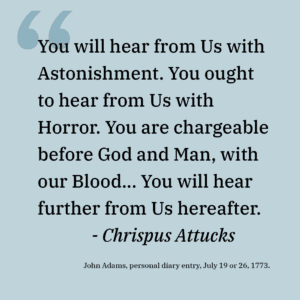

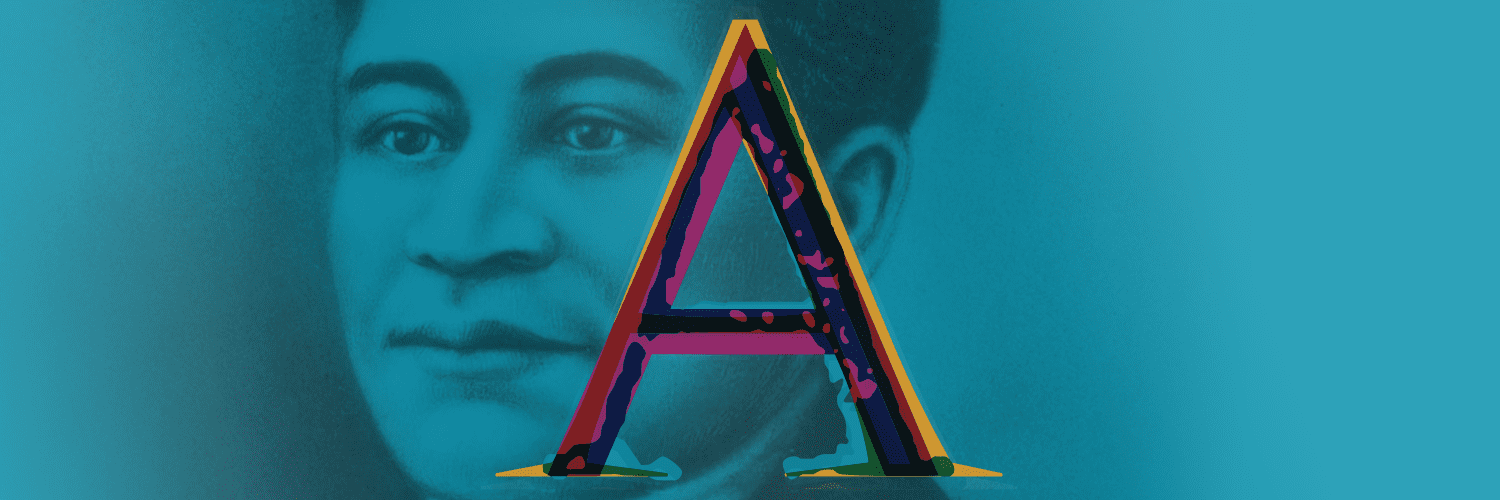

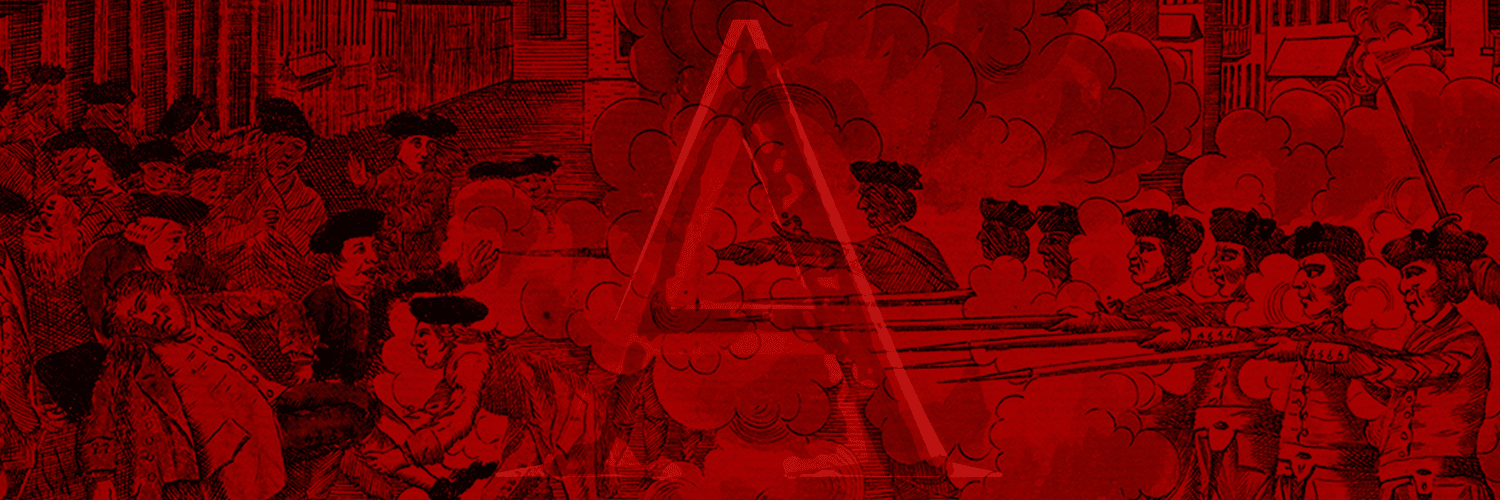

As Crispus Attucks (c. 1723-1770) approached the Customs House on March 5, 1770, Boston was an occupied town. In 1768, thousands of soldiers had been sent by the ministry to quell ongoing protests by colonists angered at their treatment as British subjects. As Parliament sought to reassert control, Bostonians became more willing to challenge its authority. An atmosphere of fear and mistrust set the stage for the violent confrontation that night, the event we now call the Boston Massacre.