Connection to Native Peoples

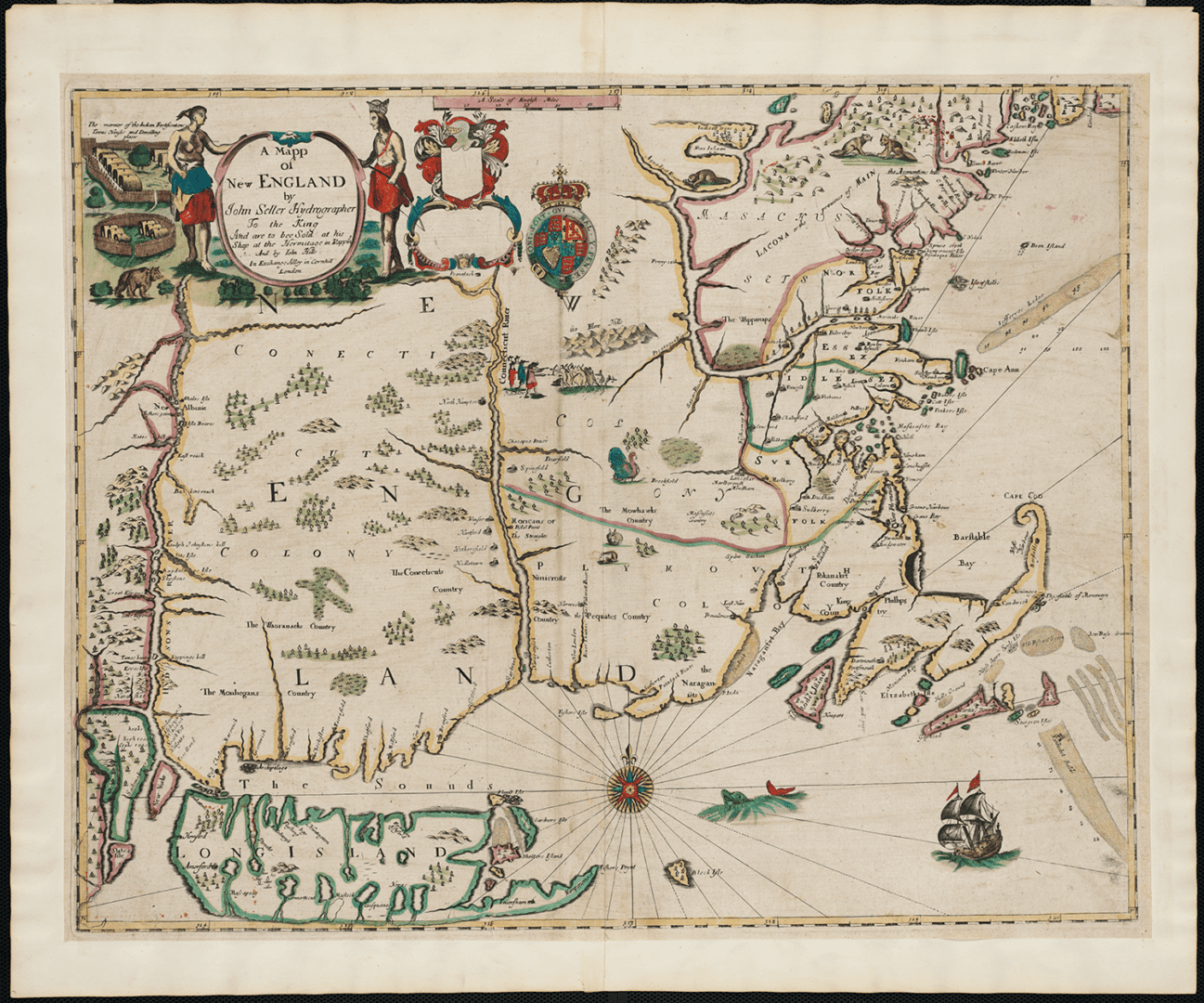

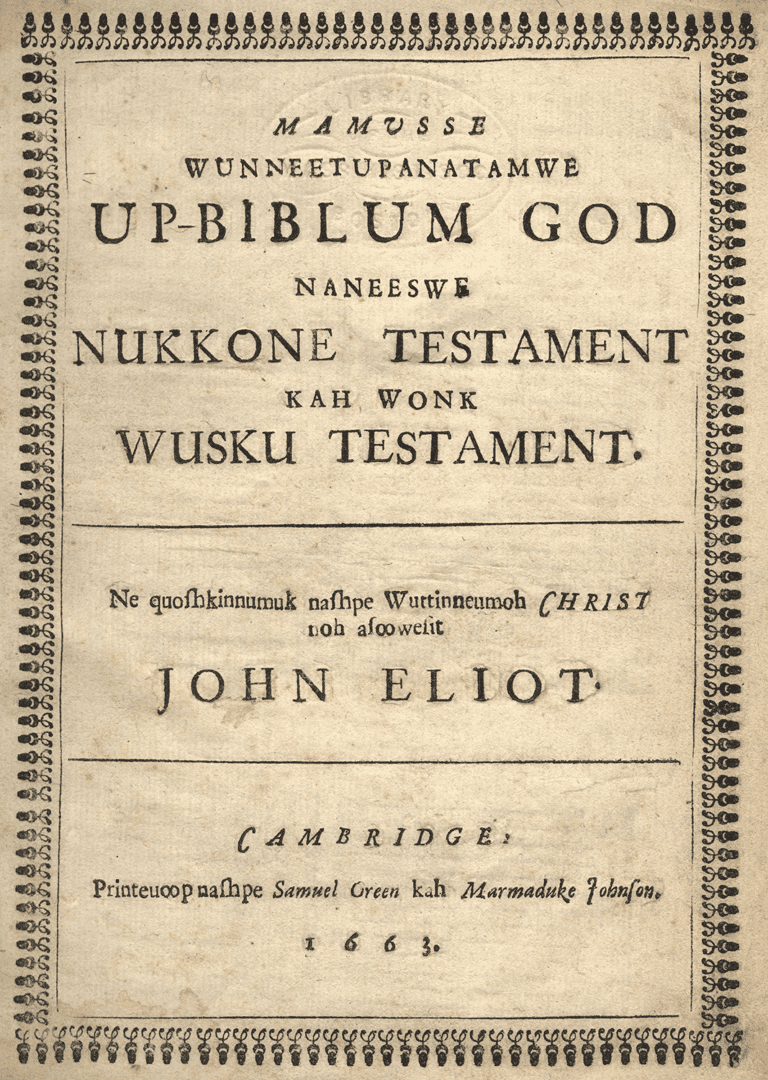

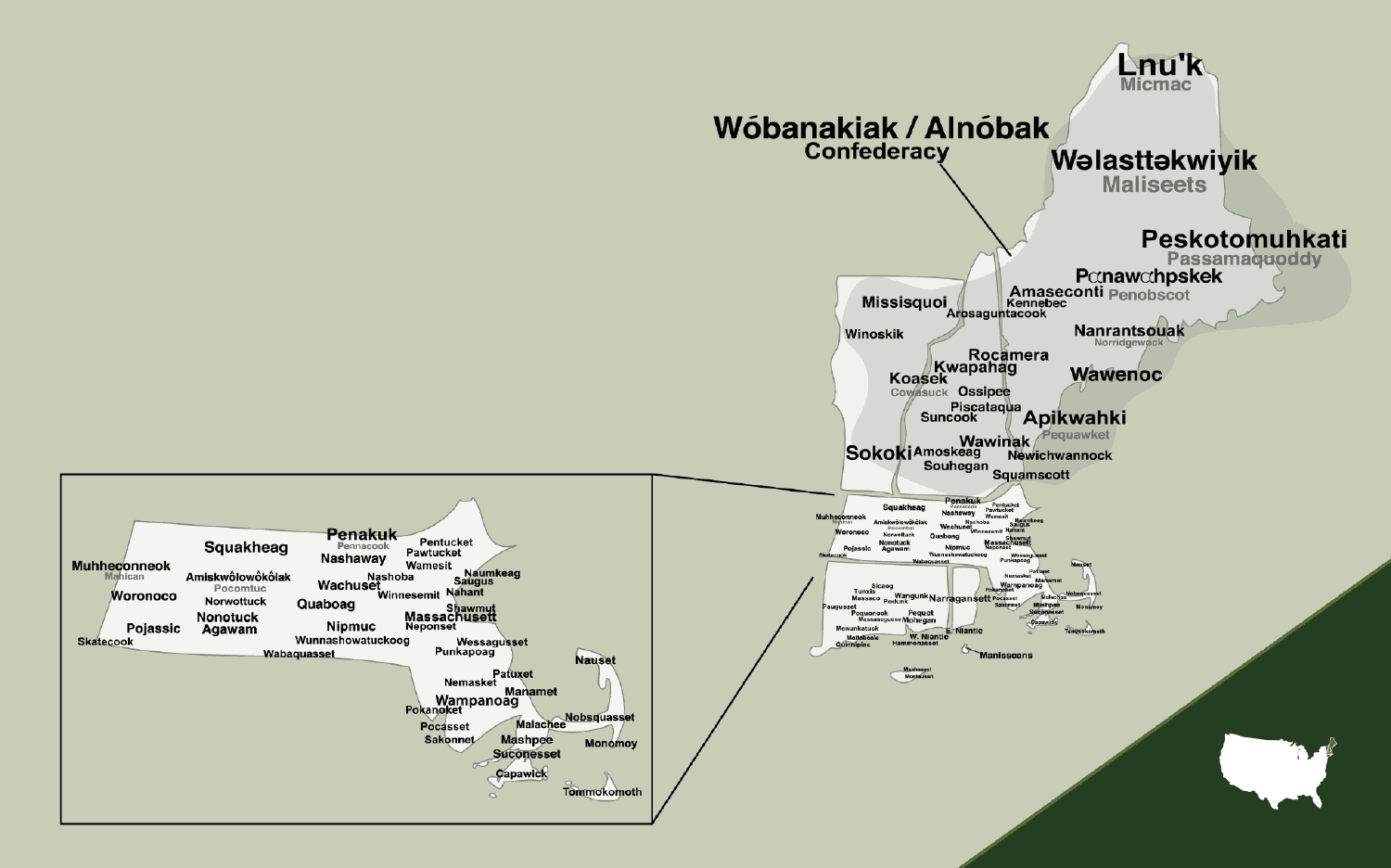

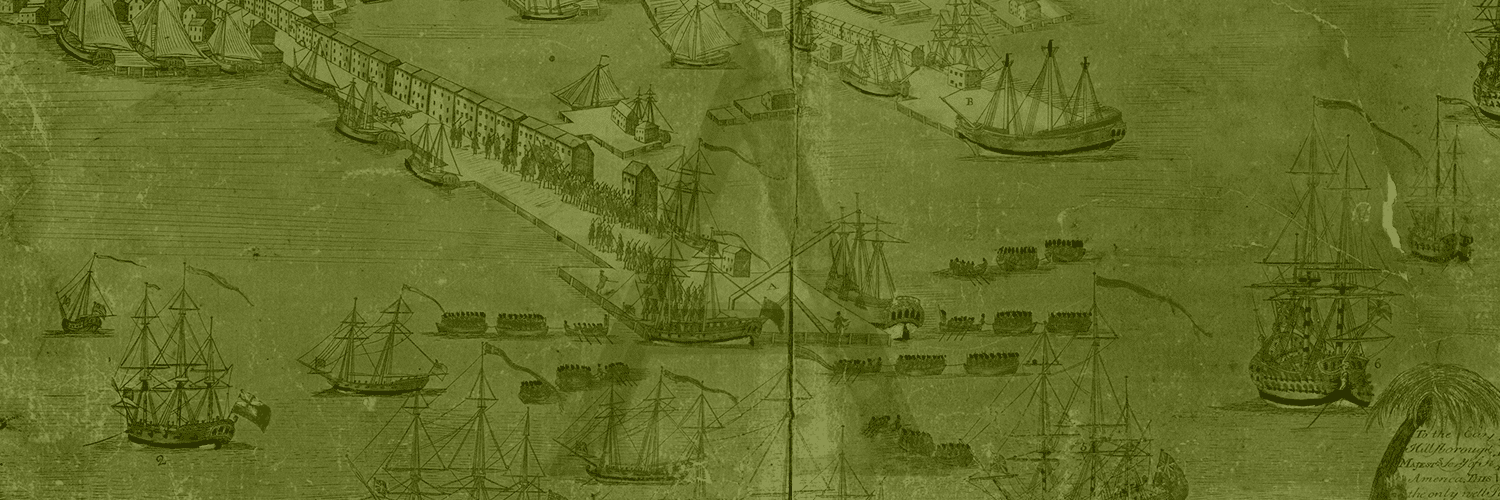

By the time of Attucks’s birth around 1723, Native people knew that contact with colonists more often led to danger rather than safety. Portuguese, Dutch, and English ships began arriving in North America in the 1500s, and about a century had passed since the Mayflower arrived on Wampanoag land in 1620. Within that time, colonists had stolen the independence of Native nations and devastated Native communities through warfare, disease, slavery, indentured servitude, kidnapping, land dispossession, and scalp bounties. Attucks would have had many potential reasons to resent both the colonists and the British.