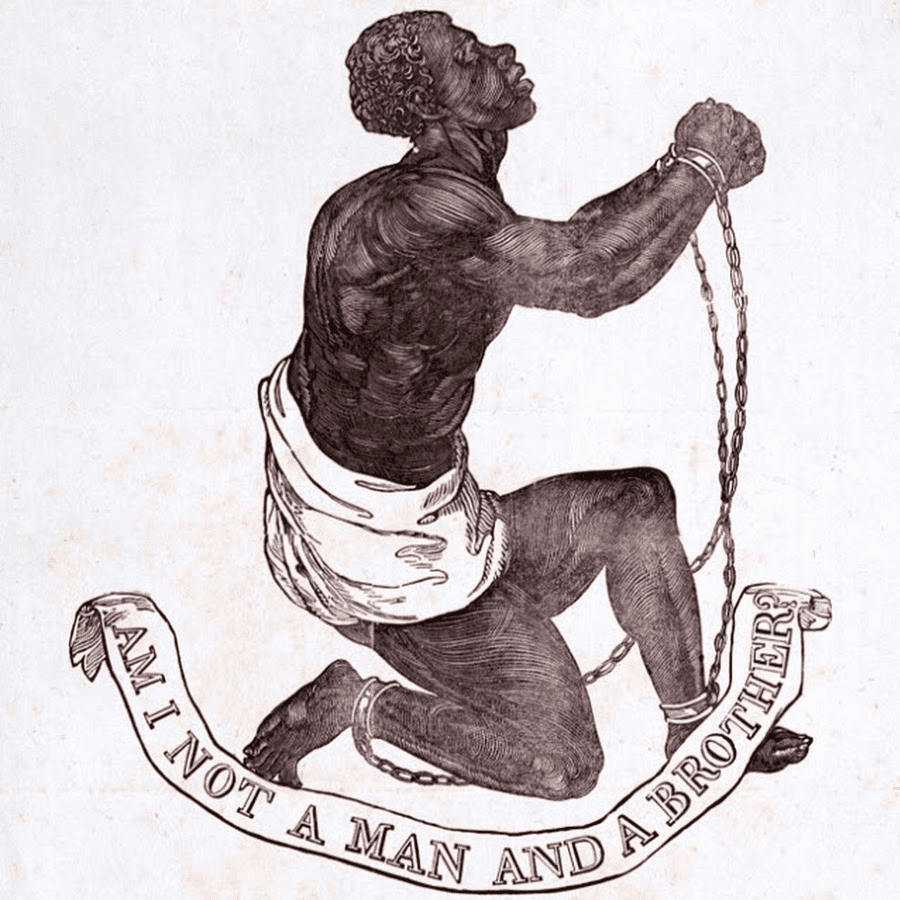

As tensions grew between Massachusetts and Britain, African-descended peoples challenged slavery through the courts. In 1765, a “mulatto” woman named Jenny Slew sued for her freedom. Because she was born to a free woman, Slew argued that she was illegally enslaved. In 1766, she won her case, making her the first person in Massachusetts to obtain freedom in a jury trial.

During the 1770s, a few years after Attucks’s death, Blacks defined republican ideas of freedom and liberty to challenge slavery across Massachusetts. In 1773, Felix Holbrook (c. 1743-1794) and Prince Hall (c. 1735-1807) petitioned the colonial legislature to end slavery. In multiple petitions, they argued that people of African descent had “in common with all other men a natural right to our freedoms.”

Although Holbrook’s and Hall’s petitions failed to end slavery, additional lawsuits succeeded once the Massachusetts constitution was ratified in 1780. Enslaved Blacks Quock Walker (1753-unknown) and Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman (c. 1744-1829) sued for their freedom based on the state constitution’s assertion that “all men are free and equal.” Both won their cases, and slavery was effectively abolished in 1783.