The Endless Endeavor: Black Bostonians and the Fight for Education Equality – Part II

Written by Lou Rocco, Director of Museum Operations & Experience

June 2024 marked the 50th anniversary of Morgan v. Hennigan, a federal court case that required Boston to desegregate its public school system through busing. Revolutionary Spaces commemorated and explored this anniversary and its history through its new exhibit, An Unfulfilled Promise: Desegregation and Busing in Boston, and on the Boston Reconsidered blog.

Since the late 18th century, Black Bostonians have had to fight for equal educational opportunities for their children. This fight included a 15-year campaign to desegregate Boston’s public schools, an effort which was codified into law in 1855. Yet, despite this important victory, Boston’s public schools once again became segregated due to residential patterns guided in part by discriminatory housing laws. Beginning in the mid-20th century, a new generation of Black parents and activists would continue the seemingly endless endeavor to fight for school desegregation and equality in Boston.

Boston, Resegregated

For nearly a generation after the passage of Massachusetts’ 1855 law prohibiting legal (“de jure”) segregation, Boston’s public schools welcomed Black and white students alike. Unfortunately, as the city’s demographics and residential patterns changed from the mid-19th through the mid-20th centuries, Boston’s public schools effectively (“de facto”) became resegregated.

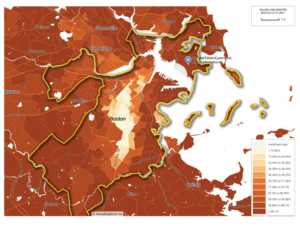

Boston’s Black population grew by 400 percent between 1865 and 1875, leading the north slope of Beacon Hill (a historically Black neighborhood) to become segregated from the rest of the city and previously integrated schools to become increasingly Black. A brief period of school integration took place at the turn of the 20th century as Black families moved to other parts of the city, including the South End and Roxbury, but resegregation quickly followed.1

As the 20th century progressed, Black families found it increasingly difficult to move to certain parts of Boston or the suburbs due to discriminatory government housing policies that restricted mortgages and loans. These policies compounded segregation as Boston’s Black population grew from around 20,000 in 1940 to more than 100,000 by 1970. The growth of the Black community enabled it to spread beyond the South End and Roxbury to the Roxbury Highlands, North Dorchester, and Mattapan. It also made it harder to ignore their demands for accountability and change.2

De Facto Segregation, Quantified

A number of reports released in the 1960s provided evidence that de facto segregation was real and produced inferior educational opportunities for Black students. These reports, issued by Citizens for Boston Public Schools, Harvard University, and The Boston Globe, collectively detailed how Black schools were overcrowded, old, poorly-maintained, and received less funding than white schools. The Harvard reports specifically found that the Boston School Committee (BSC) spent 10 percent less on textbooks in Black schools, 19 percent less for library and reference books, and 27 percent less on health care per student, while The Boston Globe report revealed that only 10 out of 2,800 Boston public school teachers were Black.3

These reports provided important evidence for Boston’s Black community as it demanded the BSC recognize and address de facto segregation and its effects on Black students and schools. For its part, the BSC dismissed these reports and their claims of de facto segregation. In the face of the BSC’s refusal to address their concerns, the Black community took efforts into their own hands.

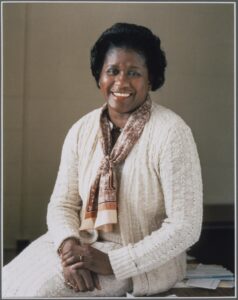

Caption: Batson (1921–2003) was a Roxbury mother who spearheaded the effort for school desegregation as Chair of the Boston NAACP’s Education Committee on Boston Public Schools and helped found METCO.

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

A New Generation Rises

One of the key organizations through which the Black community channeled its efforts was the Boston chapter of the NAACP. It kept the pressure on the BSC, leading to a pivotal meeting on June 11, 1963. At this meeting, local activists Ruth Batson and Paul Parks presented a list of 14 demands to the BSC on behalf of Boston’s Black parents. The first and most controversial was for the BSC to acknowledge that de facto segregation existed in Boston’s public schools, something the committee refused to do. It also denied that it privileged white schools over Black schools.4

A few days after the meeting, Batson and others led a School Stay Out for Freedom day, during which thousands of Black students stayed out of their public schools and attended community-organized Freedom Schools instead. Later, on September 5, Secretary for the Boston chapter of the NAACP Thomas Atkins and a dozen other NAACP members staged a 40-hour sit-in at the BSC’s offices. That same month, Batson, Atkins, and others led a march of thousands of Black and white protesters through Roxbury, ending at the dilapidated 93-year-old Sherwin School (which mysteriously burned down the next day). On February 26, 1964, a second Stay Out for Freedom day was held, this one involving more than 20,000 students.5

The second Stay Out for Freedom day compelled the state government to address de facto segregation and racial inequities in public schools. It studied the issue and produced a report titled, “Because It Is Right—Educationally.” The report found that of the state’s 55 racially imbalanced schools, 45 were located in Boston. It recommended a variety of solutions (including busing) and that the state legislature pass a law requiring school committees to eliminate racial imbalance. As with the other reports issued in the 1960s, the BSC ignored the findings of the state’s report.6

Caption: Jackson (1935–2005) was a Roxbury activist who helped lead Operation Exodus and the Roxbury-based Freedom House, a community organization which supported and helped prepare Black families for court-ordered busing.

Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute via Flickr

Operation Exodus and METCO

Boston’s Black community did not wait for the state legislature or BSC to get their children a better education within the Boston public school system. Instead, they planned to take advantage of the BSC’s open enrollment policy, wherein students could attend any school in the city if there were open seats and parents could get their children to and from the school.

Beginning in the fall of 1964 and led by Roxbury native and mother Ellen Jackson, Operation Exodus witnessed Black parents organizing private and public transit to get their children to better schools in the city. This involved identifying which schools had open seats, assigning students to appropriate schools, coordinating schedules, creating routes to and from the schools, and recruiting chaperones. Black parents funded their operation (which cost more than $60,000 per year) through community events like bake sales and fashion shows, as well as donations from benefactors. Operation Exodus served hundreds of students each year from 1965 to 1969, when it ended due to the strain on the people coordinating it. The BSC provided no support for Operation Exodus, and took efforts to obstruct it.7

A year after Operation Exodus began, Ruth Batson and other Black parents helped found the Metropolitan Council for Education Opportunity (METCO), a voluntary busing program designed to help Black students in Boston attend better schools in suburban neighborhoods. Initially funded through government and foundational grants, it began with more than 200 students in 1966, but quickly expanded to over 1,500 by the early 1970s, and 2,500 by the mid-1970s. As with Operation Exodus, the BSC provided no support for METCO. The organization continues to operate to this day, serving more than 3,200 students, two-third of whom are Black, and receiving financial support from state and city governments and private foundations.8

The Racial Imbalance Act

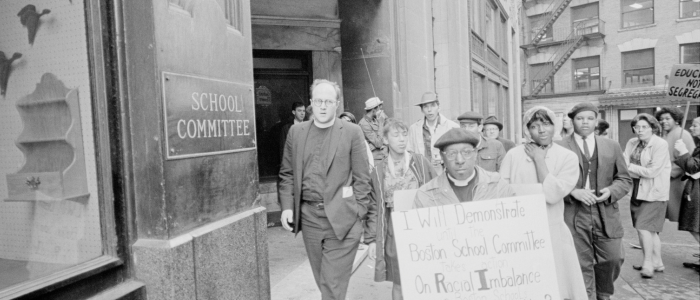

The effect of the various reports on education inequality as well as the pressure applied by the Black community eventually compelled the state legislature to act. In 1963, State Representative Royal Bolling Sr. first filed a bill to address racial imbalance in Massachusetts public schools, but it failed to pass. He refiled the bill in 1965, and following the release of the state’s report later that year, momentum for his bill grew. On April 28, 1965, Rev. Vernon Carter began picketing outside of the BSC’s headquarters on Beacon Street until the state legislature passed Rep. Bolling’s bill. On August 18, 1965, Governor John Volpe brought Rev. Carter’s 114-day picket to an end when he signed the Racial Imbalance Act (RIA) into law, making Massachusetts the first and only state in the country to pass legislation designed to proactively address school segregation.9

The RIA defined any school with more than 50 percent minority student enrollment as imbalanced, required school districts to eliminate racial imbalance, and empowered the state to withhold funding from school districts that refused or failed to do so. While it prohibited involuntary busing, it also included busing as one of the recommended solutions to racial imbalance in public schools.10

Caption: From April to August of 1965, Rev. Vernon Carter (front right) led a picket in front of the BSC’s offices to advocate for the passage of the RIA.

Courtesy Boston Public Library, Brearley Collection

Following the passage of the RIA, the BSC conceded that racial imbalance existed in Boston’s public schools, but that this was the product of residential segregation outside of its control. They also made it clear that they did not intend to comply with the law, causing the Boston public school system to lose millions of dollars in state funding and the number of racially imbalanced schools in Boston to grow from 45 in 1965 to 62 by 1971. As a result, Black students continued to go to school in aging buildings with limited curricula and higher teacher turnover. Additionally, the BSC latched onto the RIA’s recommendation of busing as one potential solution and used it to turn Bostonians against the idea of school desegregation generally.11

The constant resistance of the BSC and subsequent effects on Black childrens’ education compelled some parents to seek refuge in the courts. On March 15, 1972, the NAACP filed suit against the BSC on behalf of dozens of Black parents and students alleging racially discriminatory practices and policies. On June 22, 1974, Federal District Judge Wendell Arthur Garrity Jr. issued his opinion in the case, named Morgan v. Hennigan, finding that the BSC had, “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation […] and have intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system. Therefore the entire school system of Boston is unconstitutionally segregated.”12

Judge Garrity’s remedy for this violation was to impose a busing plan written by the State Board of Education to begin during the 1974–1975 school year. Boston’s Black community continued to advocate for its schoolchildren throughout the duration of Judge Garrity’s busing order, but by that point, most media attention was focused on white resistance to busing and the violence taking place in and around a small number of the city’s schools.

The Endless Endeavor

Boston’s public schools continue to face numerous challenges, most notably plummeting student enrollment caused by declining birth rates, high housing costs, and competition from charter schools. Unreliable bus transportation and fully serving the needs of ELL and disabled students are also key challenges. While these challenges differ from those of past generations, the endless endeavor of providing Boston’s children with a quality public education remains. And if the history of the centuries-long struggle for school desegregation in Boston shows us one thing, it is that Bostonians will continue to rise to meet these challenges.13

1. James W. Fraser, Henry L. Allen, and Sam Barnes, eds., From Common School to Magnet School: Selected Essays in the History of Boston’s Schools (Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1979), 27; James W. Fraser, Henry L. Allen, and Sam Barnes, eds., From Common School to Magnet School: Selected Essays in the History of Boston’s Schools (Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1979), 109–110.

2. Steven J.L. Taylor, Desegregation in Boston and Buffalo: The Influence of Local Leaders, (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998), 49–50; “Redlining,” Federal Reserve History, June 2, 2023, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redlining; Ronald P. Formisano, Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 25; From Common School to Magnet School, 110.

3. Jim Vrabel, A People’s History of the New Boston, by Jim Vrabel (Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 49–50; From Common School to Magnet School, 110–111; Boston Against Busing, 40–41; Mel King, Chain of Change: Struggles for Black Community Development, (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1981), 32–33.

4. “The Busing Battleground,” American Experience, aired September 11, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/busing-battleground/; A People’s History of the New Boston, 51–52.

5. “The Busing Battleground,”; Chain of Change, 32–39; From Common Schools to Magnet Schools, 113–114; Boston Against Busing, 29; A People’s History of the New Boston, 54–55; Matthew F. Delmont, Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation, (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016), 81.

6. Why Busing Failed, 81; Chain of Change, 40–41; A People’s History of the New Boston, 60.

7. Why Busing Failed, 86–90; Chain of Change, 43–44; A People’s History of the New Boston, 57–59; From Common Schools to Magnet Schools, 116–119; Desegregation in Boston and Buffalo, 42–44; Boston Against Busing, 38.

8. “The Busing Battleground,”; Why Busing Failed, 90; A People’s History of the New Boston, 59; From Common Schools to Magnet Schools, 116–119; Desegregation in Boston and Buffalo, 42–44; Boston Against Busing, 38; “Enrollment Data,” the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity, accessed September 13, 2024, https://metcoinc.org/enrollment-data/.

9. “The Busing Battleground,”; Chain of Change, 41–42; A People’s History of the New Boston, 60–61.

10. Jack Tager, Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence, (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 2001), 192; J. Anthony Lukas, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families, (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), 131;

11. “The Busing Battleground,”; Common Ground, 132; Why Busing Failed, 78–85; A People’s History of the New Boston, 171.

12. “The Busing Battleground,”; Boston Against Busing, 54; Boston Riots, 192; Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F. Supp. 410 (D. Mass. 1974), Justia, accessed August 23, 2024, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/379/410/1378130/.

13. Christopher Huffaker, “Mass. Student Enrollment Barely Budged in the Last 30 Years” Boston Globe, August 23, 2024, https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/08/23/metro/massachusetts-school-enrollment-trends/; Christopher Huffaker and James Vaznis, “About two-thirds of BPS buses were late for first day of school,” Boston Globe, September 9, 2024, https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/09/09/metro/boston-bps-buses-on-time/; Carrie Jung and Max Larkin, “What you need to know about Boston Public Schools,” WBUR, December 3, 2023, https://www.wbur.org/news/2023/09/07/boston-massachusetts-bps-system-education-students-field-guide.

Bibliography

Delmont, Matthew F. Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2016.

“Enrollment Data.” The Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity. Accessed September 13, 2024. https://metcoinc.org/enrollment-data/.

Fraser, James W., Henry L. Allen, and Sam Barnes, eds. 1979. From Common School to Magnet School: Selected Essays in the History of Boston’s Schools. Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston.

Formisano, Ronald P. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Huffaker, Christopher. “Mass. Student Enrollment Barely Budged in the Last 30 Years.” Boston Globe, August 23, 2024. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/08/23/metro/massachusetts-school-enrollment-trends/.

Huffaker, Christopher and James Vaznis. “About two-thirds of BPS buses were late for first day of school.” Boston Globe, September 9, 2024. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/09/09/metro/boston-bps-buses-on-time/.

Jung, Carrie and Max Larkin. “What you need to know about Boston Public Schools.” WBUR, December 3, 2023. https://www.wbur.org/news/2023/09/07/boston-massachusetts-bps-system-education-students-field-guide.

King, Mel. Chain of Change: Struggles for Black Community Development. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1981.

Lukas, Anthony J. Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families. New York: Vintage Books, 1986.

Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F. Supp. 410 (D. Mass. 1974). Justia. Accessed August 23, 2024. https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/379/410/1378130/.

“Redlining.” Federal Reserve History. June 2, 2023. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redlining.

Tager, Jack. Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 2001.

Taylor, Steven J. L. Desegregation in Boston and Buffalo: The Influence of Local Leaders. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1998.

“The Busing Battleground.” American Experience. Aired September 11, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/busing-battleground/.

Vrabel, Jim. A People’s History of the New Boston. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014.