The Endless Endeavor: Black Bostonians and the Fight for Education Equality – Part I

Written by Lou Rocco, Director of Museum Operations & Experience

June 2024 marked the 50th anniversary of Morgan v. Hennigan, a federal court case that required Boston to desegregate its public school system through busing. Revolutionary Spaces commemorated and explored this anniversary and its history through its new exhibit, An Unfulfilled Promise: Desegregation and Busing in Boston, and on the Boston Reconsidered blog.

Massachusetts has a well-earned reputation for being home to some of the best colleges and universities in the world. Many of these institutions are located in Boston, which has a long and storied history with education, including creating the first publicly funded schools in America. But access to this education has been a constant struggle for Boston’s Black community from the beginning. The fight for education equality has been a seemingly endless endeavor for Black Bostonians, but it is one they have consistently met with tenacity and conviction.

Prince and Primus Hall and the Establishment of Black Schools

The African Meeting House served as the second home of the African School and continued to serve as the epicenter of the Black community on Beacon Hill throughout the 19th century.

African Meeting House, ca. 1860

Josiah Johnson Hawes

VW0001.001007

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces

By the end of the 18th century, Boston’s Black community was concentrated in the North End and the north slope of Beacon Hill. Around this time, Black parents petitioned the city and the Boston School Committee (BSC) at least three times—in 1781, 1798, and 1800—for a separate school for their children. Parents sought a separate school for their children because, though there was no law prohibiting Black children from attending any public school in Boston, they often faced discrimination and bullying when they attempted to attend classes.1

After several petitions were denied by the BSC, the community opened a private school called the African School in the Beacon Hill home of Primus Hall in 1798. Primus Hall was a community leader, Revolutionary War veteran, and the son of Prince Hall, another leader in Boston’s Black community. Both men were heavily involved in the petitions calling for separate Black schools. Unfortunately, the African School, which originally operated with a white teacher, had to close after a few months due to a yellow fever outbreak.2

The African School reopened in Primus Hall’s home in 1802. Its popularity and student body grew to the point where it had to relocate to the African Meeting House, a vital gathering place and community center in Beacon Hill, in 1808. That same year, the school hired Cyrus Vassall, its first Black teacher, and by 1812 began receiving some financial support from the BSC. The annual $200 provided by the BSC was not enough to cover all costs, so private donations and a 12.5 cents per week tuition were also necessary for the upkeep of the school. Additional Black schools were established between 1817 and 1822, by which point the Boston public school system was fully segregated.3

Courtesy of Google Books

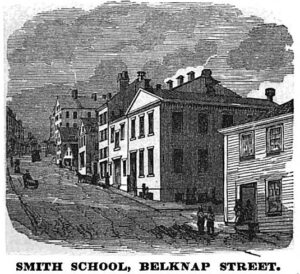

The Abiel Smith School

After years of advocacy from the Black community, the BSC approved the construction of a separate building for the education of Black children. The Abiel Smith School, named after and partially funded by a white businessman, opened in March 1835 and was the first dedicated Black public school building in Boston.4

By 1837, 300 primary and grammar school students were enrolled at the Smith School. But within a decade of its construction, the Smith School was overcrowded and showed signs of disrepair, both products of neglect from the BSC. This experience convinced many Black parents that separate schools were no longer the answer, so they petitioned the BSC to desegregate the city’s public schools in 1840, 1844, 1845, and 1846. At the same time, other members of the Black community petitioned to keep the Smith School, but install a Black headmaster. The BSC ultimately decided to grant the latter’s request, keeping the Smith School segregated but appointing Thomas Paul, Jr. as headmaster. Tensions between those who opposed and supported separate schools eventually boiled over into violence during a meeting in the African Meeting House.5

Roberts v. City of Boston

The BSC’s refusal to desegregate the city’s public schools prompted multiple responses from the Black community. At least one family sought help from the courts. In 1847, Benjamin Roberts attempted to enroll his daughter Sarah in a school near their home. Because the school in question was attended exclusively by white students, his request was denied each of the four times he submitted it. As such, Sarah had to attend the Smith School, passing five white schools closer to her home along the way. When Benjamin sent Sarah to a white school in 1848, she was sent home, after which he sued the city under an 1845 state law allowing children “unlawfully excluded from public school instruction” to recover damages.6

Roberts hired Robert Morris, one of the first Black attorneys to pass the bar in Massachusetts, to represent his family in court. After taking the Roberts’ case, Morris brought a young Charles Sumner on as his co-counsel. The two argued their case before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court on November 1, 1849. Sumner passionately argued that the entire system of segregated education violated the principle of equality found in the state constitution and harmed white and Black students alike.7

Despite their best efforts, the Court ultimately sided with the city. In his opinion, Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw agreed with the principle of equality before the law argued by Sumner, but he asserted that this principle only meant that,

Lemuel Shaw (1781–1861) was Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. His opinion in Roberts v. City of Boston helped pave the way for the “separate, but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The rights of all, as they are settled and regulated by law, are equally entitled to the paternal consideration and protection of the law, for their maintenance and security. What those rights are, to which individuals, in the infinite variety of circumstances by which they are surrounded in society, are entitled, must depend on laws adapted to their respective relations and conditions.8

In other words, it was legal to grant different rights to different categories of people based on the “conditions” of those categories, be they race, age, or sex. Shaw added that the BSC had the power to assign students to specific schools and found no reason to doubt that its rationale for keeping white and Black students segregated was, “the honest result of their experience and judgment.”9

Shaw’s decision would later be cited by the U.S. Supreme Court as evidence for the “separate, but equal” doctrine it established in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case (1896).10 In Plessy, the Court argued that the 14th Amendment secured equality before the law for white and Black Americans, but it didn’t require social equality or integration. The Court explained that,

Laws permitting, and even requiring, [the separation of the races], in places where they are liable to be brought into contact, do not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race to the other […] The most common instance of this is connected with the establishment of separate schools for white and colored children […] One of the earliest of these cases is that of Roberts v. City of Boston.11

While the Court’s decision in Roberts was a disheartening set-back, Boston’s Black community did not relent in its campaign for school desegregation.

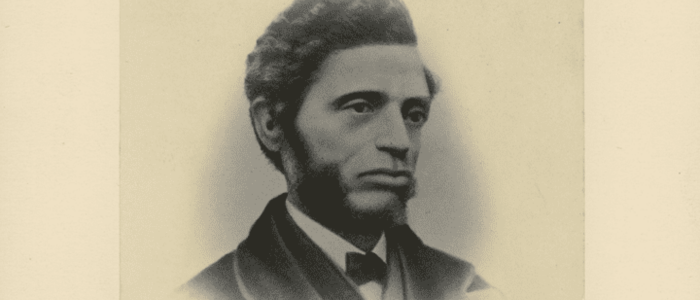

William Cooper Nell

In addition to litigation, the Black community also utilized collective action in their quest to end school segregation. One of the key figures who led this effort was William Cooper Nell. Nell was a committed activist, having organized a youth anti-slavery society and writing for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. He also attended the Smith School and experienced racial discrimination firsthand. He was a gifted student who was awarded a Franklin Medal, given to students who performed well on city-wide exams. But despite receiving the award, he was not allowed to attend the ceremony for Franklin Medal recipients at Faneuil Hall because he was Black. Nevertheless, Nell snuck into the ceremony and confronted school officials about their policy, for which they had no good response. This incident helped motivate Nell to do everything in his power to end racial segregation in education.12

William Cooper Nell (1816–1874) was one of Boston’s most significant Black abolitionists and civil rights advocates, including fighting for and securing the end of legal racial segregation in Massachusetts public schools.

Photo 81.483.

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Nell led a nearly 15-year-long campaign of protests, petitions, and boycotts in an effort to close the Smith School. In the mid-1840s, he convinced some Black parents to withdraw their students from the Smith School and founded the School Abolishing Party. These efforts eventually compelled the BSC to provide $2,000 for much needed repairs to the Smith School in 1849. Following the Roberts decision, Nell founded the Equal School Association of Boston, which petitioned the state legislature for change in the 1850s. Yet the BSC maintained its refusal to desegregate the schools, even going so far as to provide ferry money for two Black students in East Boston to attend the Smith School, rather than simply allow them to attend a white school in their neighborhood.13

Despite resistance from the BSC, Nell and his colleagues’ efforts eventually paid off when the Massachusetts state legislature passed a law in 1855 prohibiting racial segregation in public schools. On September 3, 1855, Black students were allowed to enroll in and attend previously all-white schools in their neighborhoods for the first time. It was a tremendous victory for the Black community and the cause of education equality, but it would not last.14

A New Generation Rises

The work of Prince and Primus Hall, Benjamin and Sarah Roberts, Robert Morris, William Cooper Nell, and many others illustrate the grit and determination of Boston’s Black community. Their efforts were necessary to compel America to live up to its founding ideals. Unfortunately, this generation’s victories were temporary. Part II of this blog post will examine how Boston’s public schools became resegregated despite passage of the 1855 desegregation law and how a new generation of Black leaders in the 1960s pressed the city and state to address the issue of education equality—the endless endeavor—once again.

1. James W. Fraser, Henry L. Allen, and Sam Barnes, eds., From Common School to Magnet School: Selected Essays in the History of Boston’s Schools (Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1979), 12–14, 18–20; “Primus Hall: A Revolutionary Life of Service,” National Park Service, January 8, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/primus-hall-story-map.htm.

2. From Common School to Magnet School, 20.; “Abiel Smith School,” National Park Service, January 6, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/abiel-smith-school.htm; “Primus Hall: A Revolutionary Life of Service.”

3. From Common School to Magnet School, 20–22; “Abiel Smith School.”

4. From Common School to Magnet School, 22; “Abiel Smith School.”

5. From Common School to Magnet School, 22-24; “Abiel Smith School.”; “The Sarah Roberts Case,” National Park Service, May 29, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-sarah-roberts-case.htm; “William Cooper Nell: Smith Court Leader,” National Park Service, May 29, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/articles/william-cooper-nell-smith-court-leader.htm.

6. From Common School to Magnet School, 24; “Abiel Smith School”; “The Sarah Roberts Case”; Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the Years 1843, 1844, and 1845; Together with the Rolls and Messages, (Boston: Secretary of the Commonwealth, 1845), 545, https://archive.org/details/actsresolvespass184345mass/page/544/mode/2up.

7.From Common School to Magnet School, 24; “Abiel Smith School”; “The Sarah Roberts Case.”

8. Roberts v. City of Boston, 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198 (1849), Caselaw Access Project, Harvard Law School, accessed September 4, 2024, https://cite.case.law/mass/59/198/?full_case=true&format=html.

9. From Common School to Magnet School, 24; “Abiel Smith School”; “The Sarah Roberts Case”; Roberts v. City of Boston.

10. From Common School to Magnet School, 24; “The Sarah Roberts Case.”

11. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), National Archives, accessed September 4, 2024, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/plessy-v-ferguson#transcript.

12. From Common School to Magnet School, 23; “William Cooper Nell: Smith Court Leader”; Adam Tomasi, “William Cooper Nell,” The West End Museum, accessed September 4, 2024, https://thewestendmuseum.org/history/era/west-boston/william-cooper-nell/.

13. From Common School to Magnet School, 23–26; “William Cooper Nell: Smith Court Leader.”

14. From Common School to Magnet School, 23–26; “William Cooper Nell: Smith Court Leader.”

Bibliography

“Abiel Smith School – Boston African American National Historic Site.” 2023. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/boaf/

Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the Years 1843, 1844, and 1845; Together with the Rolls and Messages. 1845. Boston: Secretary of the Commonwealth. https://archive.org/details/

Fraser, James W., Henry L. Allen, and Sam Barnes, eds. 1979. From Common School to Magnet School: Selected Essays in the History of Boston’s Schools. Boston: Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston.

“Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537.” 1896. National Archives. https://cite.case.law/mass/59/

“Roberts v. City of Boston, 59 Mass. 198, 5 Cush. 198.” 1849. Caselaw Access Project, Harvard Law School. https://cite.case.law/mass/59/

Rose, Danielle, and Anjelica Oswald. 2023. “Primus Hall: A Revolutionary Life of Service.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/

“The Sarah Roberts Case” 2024. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/

Tomasi, Adam. “William Cooper Nell.” The West End Museum. https://thewestendmuseum.org/

“William Cooper Nell: Smith Court Leader.” 2024. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/