Petitions

Inspired by The Humble Petitioner, our new exhibit now on view at the Old State House, members of our staff debated a fundamental question about the process of petitioning: Do petitions still have an important role to play in our democracy today? Read their responses here and visit the exhibit to discover your own answer to this question.

In Praise of Petitions

Nat Sheidley, President and CEO

In The Freedoms We Lost, historian Barbara Clark Smith traces the many forms of civic participation that were available to ordinary colonists before the American Revolution. While a minority of the population enjoyed the right to vote, there were many other ways in which the governed could express or withhold their consent to the decisions made by those who wielded political power. These included jury nullification, joining crowds that opposed executive orders, or participating in selective enforcement of the law at the local level. After the Revolution, Clark argues, many of these cherished forms of popular political participation came to be seen as inappropriate or impermissible. The Constitution defined the people, not the King or Parliament, as sovereign and voting as the primary vehicle by which their will should be exercised.

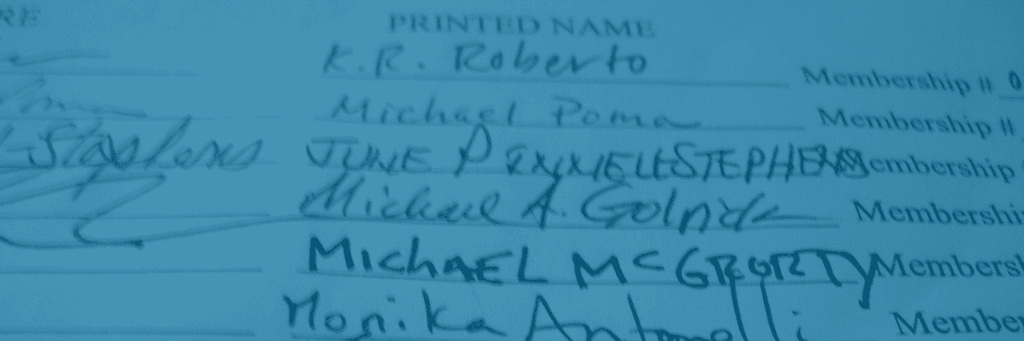

Petitions were a notable exception to this rule. As demonstrated by the many petitions on view in our new exhibit, colonists made frequent use of the petition to have their voices heard in the halls of power, and this form of civic participation only gained steam in the years after Independence. Daniel Carpenter, the Freed Professor of Government at Harvard University, has assembled an enormous database of more than half a million petitions submitted to Congress from 1789 to 1949. While some of these petitions were frivolous, many more addressed the most important political issues of their moment, from slavery and woman suffrage to banking policy and workplace rights.

The use of petitions has fallen off substantially over the past five decades, but Carpenter’s analysis suggests that this shift may not be a good thing for our democracy. Elections and voting are “episodic,” he argues in his recent book, Democracy By Petition, meaning that the voice of the people is often silent when it most needs to be heard. Petitions helped to fill this critical void during the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, not only by demanding a response from those in power but by mobilizing popular support, recruiting citizens to important causes, educating them and clarifying their thinking, and building social movements and organizations that endured long after the petitions that were their initial focus were delivered. In this sense, petitions functioned less as a tool for effecting specific policy changes and more as a vehicle for activating a deep and sustained engagement with the political process at all levels of society.

The practice of gathering signatures in support of a candidate or cause is still common in some parts of the country, and social media has made it possible for petitions to be shared more rapidly and widely. But as Carpenter’s dataset demonstrates, this form of civic engagement has clearly ebbed in recent decades. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that participation in other aspects of civic life, including voting, have also declined. So to all who are concerned about the health of our democracy, I say: grab a pen and clipboard, and start knocking on doors. The act of petitioning may have ancient roots, but it also has an important role to play in our political life today.

Petitions Without Power

Matthew Wilding, Director of Interpretation & Education

In 1893, a six-foot-tall wooden frame with two wheel-shaped spools of paper was wheeled into the United States Senate. The petition, organized by Massachusetts bicycle enthusiast Colonel Albert Pope and signed by over 150,000 cyclists, became known as “the Bicycle Petition,” and is credited with prompting the creation of a congressional road research office that led directly to the creation of federally funded paved roads and highways in the United States. One could argue that roads in America are for cyclists rather than cars due to this petition and its signers. But did the bicycle petition create paved roads? Or was the petition merely a prop utilized by legislators, no different from Rep. Katie Porter’s (CA-D) infamous whiteboard or Marjorie Taylor Greene’s Scooby Doo Meme?

I am not arguing that petitions are not useful, or in some cases effective, but to have an “important role in our democracy today,” petitions are reliant upon the actions of citizens to ensure that the representatives in our democracy are willing to hear the desires and beliefs of the people they represent, rather than their own self interests. To achieve that, the role of active citizenship–the act of not just signing the petition that your college roommate posts on social media, but making informed decisions at every level of the ballot, engaging in community meetings and electoral campaigns, and holding representatives and other citizens accountable–is important. The petition is a tool, and frankly a weak one. To be sure, it almost always has been.

It is worth noting that the petitions in The Humble Petitioner were submitted in all cases by those without the ballot at their disposal, and with few other tools at hand. It is equally worth noting that by any measurement, the majority of the petitions featured in the exhibit ultimately failed at their aims. To the extent that they did succeed, most of them succeeded as components in larger bodies of struggle. They were small, minor pieces in a multi-faceted whole. Their use today, like in the 18th century, is but one of many approaches one can take, and more than most of the other tools in the toolbox, the petition is reliant upon the grace and attention of the representatives it addresses. Other tactics: political ones like the ballot, social ones like the protest or sit-in, violent ones like the riot or even the assassination, are far more difficult to ignore, even by the most venal or corrupt among those in power.

There were doubtless petitions advocating for better access for the disabled, but were they more effective than the Capitol Crawl demonstration in getting the Americans with Disabilities Act passed? The Stamp Act Congress, formally no more than a group of British citizens petitioning their King, were formally ignored by their government, and while the Stamp Act was never implemented in the colonies, it is much more likely that this was due to the impossibility of enforcement following the Stamp Act riots of 1765 than of a petition that may or may not have ever been read. As of this writing, the leading petition on MoveOn.org features over 15,000 citizens demanding that George Santos resign from Congress. It seems unlikely that it will be a factor in his decision either way.

The petition is not a completely obsolete vehicle for making one’s voice heard, but it is by no means an “important,” or even particularly useful, tool. It is, as it has ever been, a way of pleading with those in power, of begging for scraps. In a nation where the people are sovereign, applying one’s signature to a form letter is rarely enough. The responsibility of citizenship demands more.

Click here to read more Revolutionary Conversations.