Massachusetts’ Hull Mint

Written by Lucy Pollock, Exhibits Manager

After years of outright disobedience to the Crown, Massachusetts Bay colony faced a fatal accusation from British trade official Edward Randolph: Massachusetts’ “unsurpassed misdemeanors and contempts […] amount to no less than high treason.” The current government was too independent-minded to lead a loyal British colony. Randolph recommended the government be dissolved. At the very least, he believed, the colony’s radical faction should be disenfranchised and replaced with “honest and prudent gentlemen who will with all duty receive his Majesty’s government and laws.”1 The colony was on the brink of destruction—or even worse, subjugation.

The misdemeanors Randolph spoke of were not the Boston Tea Party or Stamp Act Riots, but simple governmental functions, like coining money. Massachusetts’ Hull Mint had been secretly and illegally creating New England-branded silver coins for about 30 years at the time of Randolph’s accusation in 1681. The ‘radical faction’ had chartered the mint in order to realize the economic prosperity they had crossed the ocean to seek. The issue was simple: There was no hard currency in the colonies, which made it impossible to amass wealth.

Their solution caused another problem, though. Randolph saw their illicit coin as an attempt to create an economy—and perhaps even an entire society—outside the control of the British Empire. The King agreed, and annulled Massachusetts’ charter three years later, placing the colony more directly under his control.2 This revocation of rights remained in Massachusetts’ public memory for the coming century and made Massachusetts hypersensitive to governmental overstep. By 1776, after a decade of Parliamentary infringements, the political environment of Massachusetts was ripe for revolution.

Independent from the Start

The Massachusetts Bay colony was chartered in 1629 by King Charles I in large part as an economic venture to enrich the British Empire, while also allowing the colony’s Puritan founders to pursue a kind of religious utopia for themselves. The charters the King granted all contained a built-in check on the colony, a clause mandating that the company’s shareholders meet in England, close to the Crown for supervision. For unknown reasons (one historian speculates a “timely bribe”) this clause was left out of Massachusetts’ charter, allowing Massachusetts to have shareholder meetings in North America. This physical distance made it nearly impossible for the Crown to control the actions of the colony. To make matters worse for the king, the 1629 Charter granted colonists a good degree of self-sovereignty, allowing colonists to elect important positions like their Governor and legislatures and further reducing monarchical oversight. But, Massachusetts was still tied to Great Britain—and thus the Crown–through currency.

Sterling silver

2011.0001.002

Revolutionary Spaces – Bostonian Society

In Massachusetts’ early years, the colony still relied on British-minted and Crown-approved silver coins to facilitate trade.”4 However, these coins were limited in number since the British Empire’s territory did not include areas rich in the silver from which the coins were made. The coins that did flow into Boston when merchants bought cheap, colony-produced raw materials were quickly sent back to England when Bostonians purchased expensive English-made goods.5

Desperate for currency and the financial independence it would provide, Massachusetts turned to trading with Spanish and Portuguese merchants who paid with their abundant silver coins. Massachusetts’ economy began to flourish with more currency in circulation, reducing the colony’s reliance on trade with the British Empire.6 With this newfound wealth and independence, Massachusetts pulled further away from Britain in the form of conquering new territories, trading with indigenous nations and even fighting entire wars without British involvement.

The Hull Mint

In 1652, Massachusetts went a step further when the General Court chartered the Hull Mint. The Mint melted down all foreign coins and re-stamped them with New England branding. The mint was illegal; it was neither chartered by the Crown nor did it stamp coins with the face of the monarch, both of which were requirements for legal tender.7 But in 1652, there was no Crown to challenge the overstep since England was led by Oliver Cromwell‚—emphatically not an agent of the Crown. As Massachusetts saw it, the Hull Mint did not technically break the law.8

The Hull Mint made three types of coins: willow tree coins from 1652 to 1660, oak tree coins from 1660 to 1667, and pine tree coins from 1667 to 1682.9 These coins, branded with the words ‘New England,’ helped to further separate the region from Great Britain in the eyes of merchants and the foreign nations they traded with.

Sterling silver

1936.0033

Revolutionary Spaces – Bostonian Society

Sterling silver

1910.0023

Revolutionary Spaces – Bostonian Society

The Crown Catches On

From the 1660 Stuart Restoration through to 1674, the British government was too busy dealing with domestic and military issues to concern itself with the Hull Mint (which was definitely illegal now that the Crown had been reinstated).10 That year, Charles II established the Lords of Trade, an entity specifically created to oversee colonial affairs, and sent Edward Randolph to investigate the situation in Massachusetts. Randolph deemed the colony’s many oversteps—the Mint, compelling territories to swear allegiance to the General Court rather than the Crown, and trading with foreign powers, to name a few—as grounds for the annulment of their 1629 charter.11

The Lords themselves saw an opportunity to reassert their authority over the colonies and reap the obvious benefits of the mint. If Massachusetts issued a formal apology and minted coins with the monarch’s face, they would be allowed to retain their charter. Headstrong, the General Court refused. For more than a year, Massachusetts continued to mint coins without following either order. The royal stamp was a particular issue, with the General Court scorning, “Wee shall take [the stamp] as his Majesty’s signall ouning [owning] of us.”12

The Dreaded Dominion

The Hull Mint was not the first time Massachusetts pushed the limits of its sovereignty, but their outright refusal to submit to the Crown pushed King James II to void the colony’s charter in 1684. Massachusetts was absorbed into the Dominion of New England, a larger, more tightly controlled colony governed by Crown-appointee Sir Edmund Andros.13 Andros, dubbed by historian Mark Peterson as “tyranny embodied,” served with a hand-picked council, and importantly, without a popularly-elected body. Randolph, the very agent who advocated for the repeal of the 1629 charter, served many offices in the Dominion.14 Not only had Massachusetts lost its mint, but it also lost its charter, its elected assembly, and its status as a singular colony.

Benjamin Eliot

2009.0006

Revolutionary Spaces – Bostonian Society

The Dominion was highly unpopular and many citizens (with good reason) believed Andros acted in the best interest of his wallet rather than the best interest of the people. When mere rumors circulated that the Dominion’s founding monarch would be deposed, militias from around Massachusetts rose together to arrest and imprison Andros and Randolph.15

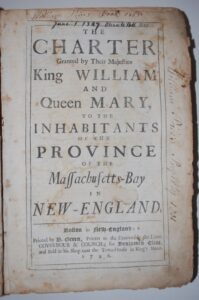

Luckily for those who participated in Boston’s hasty coup, James II was replaced by his Protestant, more sympathetic son-in-law William III. Massachusetts legislators hoped he would grant them a new charter, one that would restore the self-sovereignty they had missed in the Dominion.

After years of being on their best behavior to gain the Crown’s favor (including secretly printing the first paper money in the Western world, which would have been considered very bad behavior had the Crown found out), Massachusetts received a new charter in 1691.16 While the charter certainly granted Massachusetts more rights than they had under the Dominion, the document also took away prized pieces of their original charter. It required all legislation passed by the General Assembly to be approved by the Crown, took away citizens’ ability to elect their own Governor, and gave him veto power. The charter also specifically prohibited Massachusetts from minting currency—once again tying the financial success of the colony to the Crown.17

The Pattern Repeats

The story of the Hull Mint and the Crown’s revocation of the colony’s charter is the 17th century iteration of a pattern repeated over and over in the 18th century: Massachusetts exercises what it believes is inherent authority, and the Crown tries to regain control by taking away rights.

The Crown slowly docked Massachusetts’ power from 1764 onward, but Massachusetts responded to each act, duty, and policy change with intense objection. The traumatic disenfranchisement of the Dominion of New England left Massachusetts hyper-aware of threats to sovereignty. From the House Circular Letter in 1768 to the Body of the People meetings in 1773, Massachusetts responded to perceived threats to their sovereignty with legal (and sometimes extra-legal) action, leading to even more punishment from Great Britain. Soon, after a decade of gradual disenfranchisement, Massachusetts’ 18th century “radical faction” decided that the only solution was to break entirely from the British Empire.

1 Orla Alamon Towns, Edward Randolph and his Relation to the Colony of Massachusetts (University of Illinois, 1917), https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/52264/bitstreams/151065/object?dl=1.

2 Jonathan Edward Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne’: The Massachusetts Mint and the Battle over Sovereignty, 1652-1691,” The New England Quarterly 87, no. 3 (2014): 507, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43285101.

3 Ronald Dale Karr, “The Missing Clause: Myth and the Massachusetts Bay Charter of 1629,” The New England Quarterly 77, no. 1 (2004): 89-91, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1559688.

4 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 492.

5 Mark Peterson, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865 (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019), 47.

6 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 492.

7 “Catalogue description: Records of the Royal Mint,” The National Archives, accessed March 23, 2024, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C207.

8 “Mediation and the second Civil War of Oliver Cromwell,” Britannica, accessed April 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oliver-Cromwell/Mediation-and-the-second-Civil-War.

9 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 493-495.

10 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 505.

11 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 509-510 and Peterson, The City-State of Boston, 145.

12 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 509-512.

13 Barth, “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne,” 517.

14 Peterson, The City-State of Boston, 166, 170.

15 Peterson, The City-State of Boston, 166-171.

16 See: Dror Goldberg, “The Massachusetts Paper Money of 1690” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 4 (2009): 1092–1106, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25654034.

17 “The Charter of Massachusetts Bay – 1691,” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, accessed March 23, 2024. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass07.asp and Peterson, The City-State of Boston, 173

Bibliography

Barth, Jonathan Edward. “‘A Peculiar Stampe of Our Owne’: The Massachusetts Mint and the Battle over Sovereignty, 1652-1691.” The New England Quarterly 87, no. 3 (2014): 490–525. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43285101

Britannica. “Mediation and the second Civil War of Oliver Cromwell.” Accessed April 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Oliver-Cromwell/Mediation-and-the-second-Civil-War

Goldberg, Dror. “The Massachusetts Paper Money of 1690.” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 4 (2009): 1092–1106. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25654034.

Jordan, Louis. “Introduction to Early Massachusetts Currency.” Colonial Currency. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://coins.nd.edu/ColCurrency/CurrencyIntros/CurrencyIntro.html

Karr, Ronald Dale. “The Missing Clause: Myth and the Massachusetts Bay Charter of 1629.” The New England Quarterly 77, no. 1 (2004): 89–107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1559688.

Massachusetts Historical Society. “I. Adams’ Original Draft.” Papers of John Adams, volume 1. Accessed March 27, 2024. https://www.masshist.org/publications/adams-papers/index.php/view/ADMS-06-01-02-0054-0002.

Peterson, Mark. The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865. Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019.

The National Archives. “Catalogue description: Records of the Royal Mint.” Accessed March 23, 2024. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C207

Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library. “The Charter of Massachusetts Bay – 1691.” The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History, and Diplomacy. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/17th_century/mass07.asp

Read More Boston Reconsidered Blogs →