How was Mental Illness Viewed in Colonial Massachusetts?

Written by Lucy Pollock, Exhibits Manager

Revolutionary Spaces is collaborating with the National Museum of Mental Health Project to share the story of James Otis Jr., a patriot who lived with a mental health condition. This post is part of a series of blogs that supplement the online exhibit Patriot, Hero, Distracted Person: James Otis, Jr. and Mental Health in the Eighteenth Century.

A surprisingly star-studded list of colonial Bostonians lived with mental illness: Lydia Mather, third wife to Cotton Mather; Thomas Hancock, uncle of John Hancock; Thomas Eayres, son-in-law to Paul Revere; and, most famously, James Otis, Jr.1 These individuals only scratch the surface. Dozens of lesser known colonists whose entire historical record consists only of birth, baptism, marriage, and death dates, are also recorded as being non compos mentis, or “not of sound mind.”

Then as now, mental illness was a part of daily life. We see it today for what it is: a normal, treatable part of human experience. But how did seventeenth and eighteenth century colonists, who lived in a completely different world, record, understand, and explain mental illness?

Otis is probably the most well known colonist who lived with a mental illness, and continued to be involved in public life for years after being declared non compos mentis.

Courtesy New York Public Library

“Distracted People” in Colonial Massachusetts

Lacking our modern diagnostic distinctions, colonists often referred to almost any mental illness as “distraction,” “melancholy,” or “madness,” making it difficult to pinpoint what conditions were common.

Fortunately for historians, colonists were proficient documentarians. Diaries and letters noted when a community member’s behavior or mood shifted, but even so, these descriptions are frustratingly vague: people suffered from “fits,” “lethargy,” “nervous disorders,” and “languishing.”2 Historians deduce that these probably fit the larger category of mood disorders, including various depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorders.

Government records paint a different, though no more detailed image. Local courts only involved themselves in cases of more outwardly obvious disorders, such as when someone became violent or unable to care for themselves. Very few diagnostic details are apparent in these records. But occasionally, amidst repetitive reports of people being “incapable of taking Care either of Her person or Estate,” we catch glimmers of personal stories. In 1736, Henry Dove alternated between “lucid intervals” and being too “wild and ungovernable” to care for himself.3 In 1767, Michael Carney fell into a cistern and lost his memory.4 In 1773, Elder William Parkman was so old and ill, “so broken in Mind,” that he was assigned a guardian and, like the others, declared non compos mentis.5

Puritan Sympathies

It’s hard to believe the Puritan society that produced sermons like Jonathan Edwards’ Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God and Cotton Mathers’ The Vial Poured Out Upon the Sea (and this author’s personal favorite, William Cooper’s Man Humbled by Being Compar’d to a Worm) could be anything warmer than frigid toward mental illness. Though treatment options were as primitive as expected for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, colonial New England was a relatively sympathetic place for people living with mental disorders.

Colonists who were declared non compos mentis don’t appear to have been ostracized or abused by their communities. Lower and middle-class colonists often stayed with their communities and continued their daily lives under the assumption that their disorder was temporary. Sometimes, as in the case of Reverend Samuel Checkley, the community made accommodations. After a series of personal losses in the 1750s, Checkley found himself unable to address his congregation without weeping. His sermons soon became almost unintelligible, but instead of replacing Checkley, the congregation hired someone to help him.6

Historian Mary Ann Jimenez asserts that Puritanism itself led to this mindset. In a society that believed deeply in predestination, there was little room for perceived individual decision making. Good or bad behavior was proof of salvation or damnation, both for people with mental illness and their caretakers. A lack of self-control wasn’t threatening if it could be explained as a manifestation of God or the Devil’s will, and sympathy was a spiritual duty for surrounding community members to prove their own salvation.7

“Irregular Particles” and “Animal Spirits”

Although many colonists believed there was a religious reason for mental illness, many also believed it had a physical cause. Especially during the Age of Enlightenment, colonists saw the mind and body as increasingly interconnected, and conceded that the physical world, and even trauma, could influence mental health.

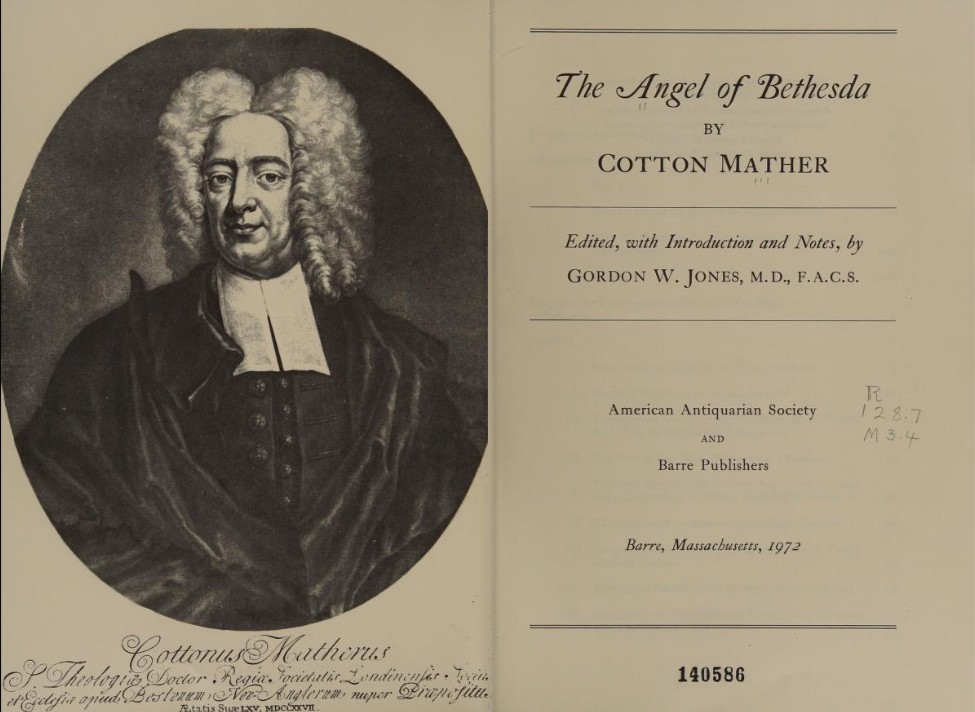

In The Angel of Bethesda, Puritan minister Cotton Mather claimed “madness” was caused by “Irregular Particles” in the blood, which fired up the “Animal Spirits.” Mather also suggests a range of secular, physical (almost too physical) treatments: salivation and bloodletting, concoctions of whey and water-lillies, even laying a “reeking hott” swallow onto the subject’s shaved head. Mather does note that demons were sometimes to blame (in which case prayer with fasting is the best cure), but he generally frames mental illness as something with a physical cause and physical treatment.8

Though very rare, colonists also sometimes linked trauma and mental health. In 1642, John Winthrop noted that one of his fellow colonists’ daughters “went mad” after witnessing two of her sisters being abused “by diverse lewd persons, and filthiness in his family.”9

No, it’s Not Witchcraft: Women with Mental Illnesses

According to historian Lyle Koehler, 81 percent of the “distracted” people in seventeenth century New England were women. When Koehler examined other British colonial regions, the imbalance flipped, showing an overwhelming majority of men in every other instance. What was it about New England that led to this jarring statistic? Historians aren’t exactly sure, but they do know one thing: it wasn’t the belief in witchcraft.

While demonic possession and witchcraft may have been considered as causes, records do not show that women declared non compos mentis were usually, or even frequently, accused of being witches.10 In fact, when the court heard cases of suspected witches, they approached with skepticism and favored a physical explanation of “insanity” over the occult.11

Charles C.J. Hoffbauer X0370

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces

Too Good to Last

Massachusetts has a long, complex history with mental healthcare. After becoming part of the United States, the Industrial Revolution changed the social order of Massachusetts even further, and the tight social structure of Puritan society fell apart. The commonwealth mindset that was sympathetic to “distracted people” gave way to a culture of individualism that alienated and institutionalized “maniacs.” As medical curiosity grew, Massachusetts opened some of the first institutions for people with mental illnesses, including the Worcester (1833), Danvers (1878), and Medfield (1892) State Hospitals. But this robust (though deeply problematic) infrastructure was not the first system to exist in Massachusetts.

In the final blog post in this series, we will examine the government and social structures in place in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to support the people with mental illness and their families, from alms and workhouses to guardianship and community-based care.

- Nina Rodwin, “Not in His Right Mind”: Paul Revere and Mental Illness in the Early Republic. The Revere Express Blog. September 5, 2020. https://www.paulreverehouse.org/not-in-his-right-mind-paul-revere-and-mental-illness-in-the-early-republic/, Virginia Bernhard, “Cotton Mather’s “Most Unhappy Wife”: Reflections on the Uses of Historical Evidence. The New England Quarterly 60, no. 3 (September 1987), 341-362. https://doi-org.ezproxy.bpl.org/10.2307/365020, Albert Deutsch, The Mentally Ill in America: A History of their Care and Treatment from Colonial Times. Cambridge University Press: New York (1949), 68-69 https://archive.org/details/mentallyilliname00deut, and Patriot, Hero, Distracted Person: James Otis, Jr. and Mental Health in the Eighteenth Century. National Museum of Mental Health Project and Revolutionary Spaces. Accessed November 14, 2025. http://nmmhproject.org/jamesotisjr

- Larry D. Eldridge, “‘Crazy Brained’: Mental Illness in Colonial America.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 70, no. 3 (1996): 366-367. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44444673. 384-386

- Boston Record Commissioners, “A report of the record commissioners of the city of Boston : containing the records of Boston selectmen 1716-1736.” Rockwell and Churchill (1885)

- Boston Record Commissioners, “A report of the record commissioners of the city of Boston : containing the records of Boston selectmen 1764-1768.” Rockwell and Churchill (1889) https://archive.org/details/reportofrecordco2017bost

- Boston Record Commissioners, “A report of the record commissioners of the city of Boston : containing the selectmen’s minutes from 1769 through April, 1775.” Rockwell and Churchill (1893) https://archive.org/details/reportofrecordco23bost

- Mary Ann Jimenez, “Madness in Early America: Insanity in Massachusetts from 1700 to 1830,” Journal of Social History 20, no. 1 (August 1986). 26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3788275.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A9aefbf3225f6f4f1f989ad6aa678a480&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_phrase_search%2Fcontrol&initiator=&acceptTC=1

- Mary Ann Jimenez, “Community Mental Health: A View from American History” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 15, no. 4 (December 1988). 128-129. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1873&context=jssw

- Cotton Mather, The Angel of Bethesda. American Antiquarian Society and Barre Publishers (1972), 129-132. https://archive.org/details/angelofbethesda0000unse

- Eldridge, “Crazy Brained,” 372

- “Salem Witch Trials,” Boston Public Library, accessed November 15, 2025. https://guides.bpl.org/salemwitchtrials/accusersandaccused

- Eldridge, “Crazy Brained,” 370-371