Conserving the Memory of Crispus Attucks

Written by Jill Conley, Registrar & Collections Manager, and Nicole McAllister, Special Collections Librarian

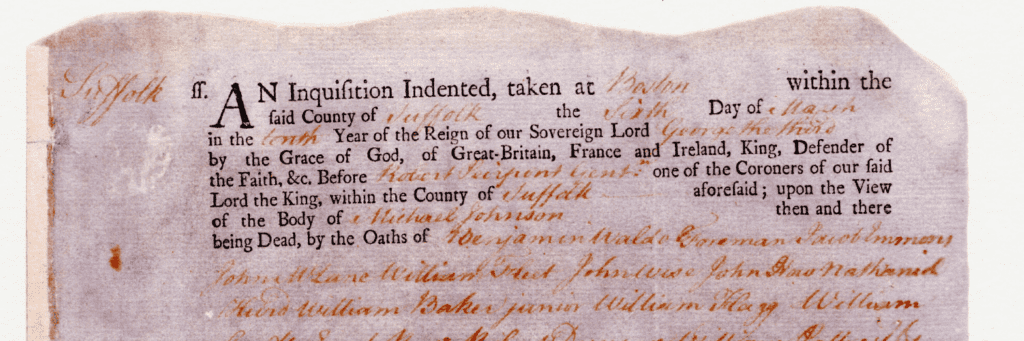

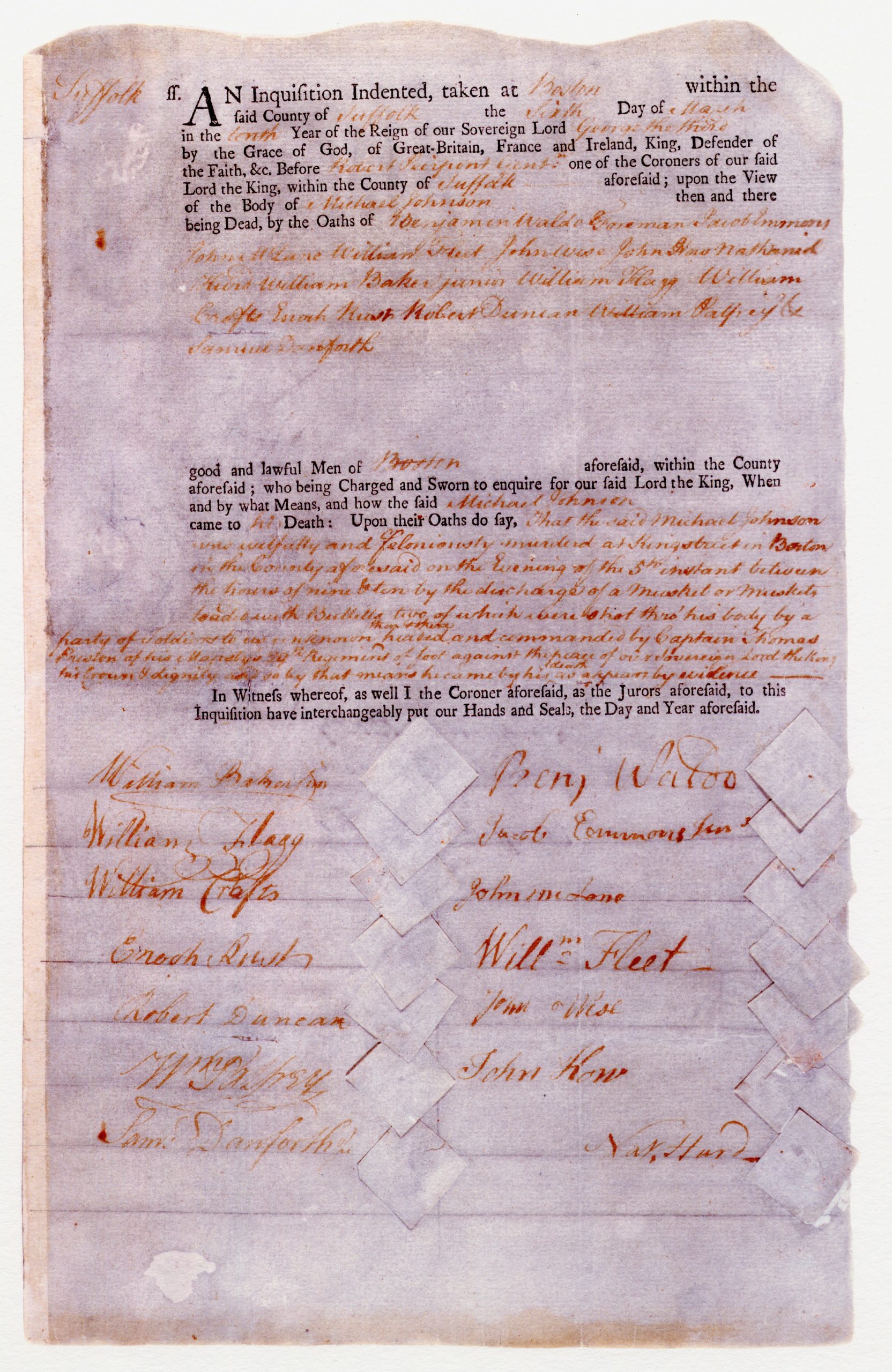

On March 6, 1770, the day after the Boston Massacre, the coroner filed an autopsy report for Crispus Attucks, a formerly enslaved man of African and Native descent who was the first to die at the “Incident on King Street.” In the autopsy report, Attucks is identified as “Michael Johnson,” a name which he might have been using to protect himself from being re-enslaved. Within days of the report’s release, newspapers in both Boston and Philadelphia identified the man known as Michael Johnson as Crispus Attucks.

It is pretty incredible that this particular document survived and found its way into the collection of Revolutionary Spaces (by way of the former Bostonian Society). In general, it’s rare to have any forensic evidence from the 18th century, but this particular document was used in the trial of the Boston Massacre – one of the most pivotal events leading up to the American Revolution. This document gives us an opportunity to have a tangible connection to Crispus Attucks, and it speaks directly to the question of how we remember the oftentimes invisible, yet important role so many people played in the events of our nation’s founding.

The autopsy document – a copy of which is on display in our Reflecting Attucks exhibit – is titled “Verdict of the Coroner’s Jury Upon Body of Michael Johnson [Crispus Attucks],” and includes a description of how he died, and the signatures of 14 men. It was purchased by the Bostonian Society in 1891 and even then was only considered to be in “fair” condition. Still, other museums have borrowed this historically important document over the years to support their own temporary exhibitions. For example, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. included the autopsy report in “The Afro-American in the Age of the Revolution, 1770-1800,” which was on view from February to September 1973.

In 1992, the document was sent to the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) in Andover, Massachusetts, for conservation treatment. Previous handling and other treatments had caused damage, so NEDCC was tasked with stabilizing and cleaning the document. The back had previously been layered with Japanese paper that was causing it to curl dramatically. The front was soiled with grime and soot. The document had been folded many times and probably had many breaks and tears which were being held together by the Japanese paper backing.

The NEDCC’s treatment began by removing surface soil using special dry cleaning techniques – the document was immersed in a water bath and then an alkaline bath to clean it, reduce the acidity of the paper, and relax the imperfections. To further smooth out the document, it was flattened between blotters (soft pieces of paper designed to pull excess moisture from the document) under pressure. The document was then backed with lightweight Japanese paper to reinforce the sheet and to mend tears, while still allowing the text on the back to be legible through the backing. Finally, the document was mounted on an acid-free mat using Japanese paper hinges and wheat starch paste.

Learn more about this cleaning process via the New York Public Library.

While conservation work is unable to completely prevent the eventual long-term decay of the Coroner’s Report, the work done in 1992 will certainly slow it down. Our collections staff are also all well-versed in proper care of historic documents, ensuring that this important document is around for decades to come.