Bunker Hill in Four Objects

Written by Lucy Pollock, Exhibits Manager

Revolutionary Spaces’ collection boasts a compelling and diverse set of objects related to the Battle of Bunker Hill. Eerily calm prints of a forested Bunker Hill give us the view from above, and cannonballs and powder horns let us zoom in on specific stories. While most of us are more used to reading a book—or, for those primary source lovers, first-hand accounts of the battle—a whole new perspective opens up for us when we let the objects lead the way.

1887.0158

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces

Anonymous Artillery

While muskets, bayonets, and gunpowder might come to mind first when imagining the warfare of the American Revolution, cannons played a huge part in winning or losing battles—and in devastating bodies, buildings, and landscapes.

At Bunker Hill, the provincial (colonial) forces may have had up to six cannons at their redoubt—particularly effective against lines of slow-moving British soldiers. But six cannons sharing a limited supply of gunpowder with muskets and pistols were nothing compared to the extensive British artillery. During the battle, opposing cannons rained down on Bunker Hill from Copp’s Hill Battery across the river and warships in Boston Harbor. The mere sound of the British cannonade caused some provincial soldiers to flee before the battle had even started. The first person to die on the battlefield was supposedly struck in the head by a cannonball. Cannons aimed at the settlement of Charlestown ignited fires that burned the town to ashes.1

Though the British had more artillery, they did not necessarily have the right ammunition. Many of the cannons were supplied with the wrong sized cannonballs, forcing British troops to substitute in grapeshot; essentially a shotgun round for a cannon.2 Grapeshot was horrifyingly effective at close range against a closely-packed enemy, busting holes through lines of infantrymen and tearing them apart in the process.3 The grapeshot pictured above was found at the battlefield after the fighting had ended. While we can’t know for sure who the grapeshot was fired by, or if it was even fired at all, it remains as physical proof of the devastation and waste of warfare.

Healers on the Hill

0021.1886

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces

During and after the battle, doctors exhausted themselves saving as many people as they could. Though it’s easy (and morbidly satisfying) to dwell on the rough, unsanitary conditions of battlefield medicine, these men risked their lives to treat the wounded in the best way they knew how. Wielding sometimes frightening tools like this surgeon’s amputation saw, the doctors at Bunker Hill saved innumerable lives. Among these healers were Dr. Thomas Kittredge, the first in a long familial line of physicians who contributed to the medical field, and Dr. David Jones, owner of this surgeon’s saw and student of Dr. Joseph Warren.4

The wounded from Bunker Hill were cared for by Massachusetts regimental doctors at Massachusetts regimental hospitals; a system designed for patching up colonists local to the area. Because of the incredible bloodshed at Bunker Hill, the Continental Congress realized that the coming war would need a more robust medical approach than taken by the Massachusetts doctors. Their actions at Bunker Hill, though heroic, just couldn’t scale to an inter-colonial war.

On July 27, 1775, the Continental Congress created the Continental Army Medical Department (CAMD) in an attempt to proactively organize hundreds of trained physicians and volunteers and establish supply chains. They selected Massachusetts physician (and later traitor to the patriot cause) Benjamin Church as the department’s first Director General and Chief Physician. While a good idea in theory, the legislation was vague, contradictory, and confusing; a product of the logistical nightmare that was combining the resources and ambitions of 13 separate colonies.5 Over the coming decades, Americans continued to struggle to unite their states in ways that satisfied everyone, making the creation of the CAMD the first of many pieces of legislation to divide Americans.

1940.0010

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces

A Monumental Task

After the Revolutionary War, New Englanders who fought in or remembered the Battle of Bunker Hill grappled with the battle’s legacy and contemplated the new nation they had risked everything for. Without the common enemy of Great Britain to unify them, tensions between the colonies mounted throughout the early 19th century. Many hoped that commemorating this shared national experience would help unite the nation.

The Bunker Hill Monument Association (BHMA) was formed in 1823 by a group of Bostonian men in order to build a monument on the battlefield and preserve the space for future generations. Once the cornerstone was laid and the final design was chosen, the BHMA turned their attention toward everyone’s favorite part of a project: fundraising.6

Despite nearly 15 years of raising money for the monument, part of which included selling off most of the battlefield for private housing, the BHMA had yet to finish the monument by 1840. While women had been allowed to participate on a smaller scale for fundraising, their efforts to run subscription campaigns were criticized by men who believed it was inappropriate for women to participate in the public and financial spheres.

In the summer of 1840, BHMA’s attitude changed. Staring down a $30,000 fundraising goal to unlock previously pledged funding, BHMA decided to give women the opportunity to prove their fundraising capabilities, albeit in a socially accepted format. A women-led committee was formed to coordinate a large-scale fundraising event, a “Ladies’ Fair,” to meet the goal.

Only six weeks after the committee was formed, the ladies successfully mounted the Bunker Hill Monument Fair. Sixty-three fair tables were set up on the second floor of Quincy Market, where women sold crafts including needlework, household items, and dolls, like the one pictured here. Over 35,000 visitors from across New England purchased admission tickets and goods from vendors, and within five days, the committee smashed the $30,000 fundraising goal that the BHMA had struggled to achieve for years.7

“One Country, One Constitution, One Destiny”

J. Fisher and N. Currier

1894.0054.002

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces

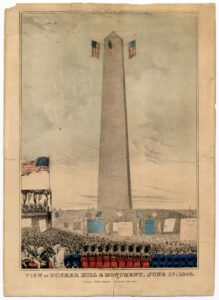

To present-day Bostonians seeing this print in spring of 2025, the flags flanking the monument look pretty familiar. Since early May of 2025, two Betsy Ross U.S. flags have been hanging from the observation deck, just as they did for the monument’s dedication ceremony in 1843. Though today’s visitors see more picnickers and school groups than soldiers and horses, the print demonstrates how the Bunker Hill monument has defined the Charlestown skyline since the mid-19th century.

The monument’s dedication ceremony drew a crowd of more than 100,000 people, including President John Tyler and statesman Daniel Webster, who delivered a stirring speech from a platform seen in the print to the left of the monument. In his speech, he emphasized national unity during a time of seemingly insurmountable division in the country. Webster chose to see the monument as a place for all Americans, promising, “wherever else you may be strangers, here you are all at home.”8

Americans will be celebrating, commemorating, and contemplating many 250th anniversaries over the next few years, including the Battle of Bunker Hill. As the 13 colonies moved forward together after Bunker Hill, compromise was necessary to navigate the challenges of creating a new, functional, more free nation. Generations of Americans continued this tradition of compromise and willingness to understand each other. As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, we reflect upon the words Daniel Webster spoke nearly 200 years ago: despite our differences, Americans share “One Country, One Constitution, and One Destiny.”9

1 Di Spigna, Christian. Founding Martyr: The Life and Death of Dr. Joseph Warren, the American Revolution’s Lost Hero. Crown Publishers, 2018. 180-182

Bernard Bailyn. “The Battle of Bunker Hill.” Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.masshist.org/features/bunker-hill/essay

2 “Bunker Hill.” Museum of the American Revolution. June 17, 2014. Accessed June 10, 2025.

https://www.amrevmuseum.org/read-the-revolution/bunker-hill.

3 “Grapeshot.” Britannica. Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/technology/grapeshot Brandon Fisichella. “A Terrible Hailstorm: Grapeshot in Linear Warfare, as portrayed in “Union of Salvation.” Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0hP3SeJIVFk.

4 “250th Anniversary of the American Revolution.” North Andover Historical Society. Accessed June 10, 2025. https://www.northandoverhistoricalsociety.org/rev-250

5 Gillett, Mary C. “Chapter 2” from “The Army Medical Department: 1775-1818.” AMEDD Center of History & Heritage. https://achh.army.mil/history/book-rev-gillett1-ch2

Clark, Ellen McCallister. Saving Soldiers: Medical Practice in the Revolutionary War. American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati, Inc. https://www.americanrevolutioninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Saving-Soldiers-catalog.pdf

6 “Building the Bunker Hill Monument.” National Park Service. Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/building-the-bunker-hill-monument.htm

7 “The Bunker Hill Monument Fair of September 1840.” National Park Service. Accessed June 4, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/bunker-hill-monument-fair.htm

8 “Dedication Speech for the Unveiling of the Bunker Hill Monument.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/primary-sources/dedication-speech-unveiling-bunker-hill-monument

9 Ibid.