Why did James Otis, Jr. Live in Andover, Massachusetts? Explore the Town Where the Famous Patriot Spent his Last Years

Written by Lucy Pollock, Exhibits Manager

Revolutionary Spaces is collaborating with the National Museum of Mental Health Project to share the story of James Otis Jr., a patriot who lived with a mental health condition. This post is part of a series of blogs that supplement the exhibit Patriot, Hero, Distracted Person: James Otis, Jr. and Mental Health in the Eighteenth Century.

In a world full of houses advertising “George Washington Slept Here,” Massachusetts towns boast: “James Otis, Jr. Lived Here While Recovering from his Mental Illness.” At least three towns can, anyway: Hull (ca. 1771-1772), Barnstable, (ca. 1775-1778) and Andover (ca.1779-1783) were chosen by Otis’ brother and guardian Samuel Allyne to be places of respite and peace for Otis in his final years. Andover in particular became famous for it, and was even referred to as the “Massachusetts bedlam” in the early nineteenth century.

After years of stress and anxiety over the political situation in 1760s Boston, Otis’ emotional state was fragile. Prone to outbursts from his naturally hot temper, Otis’ words caught up to him on September 5, 1769, when customs official John Robinson beat him with a cane. The assault caused a traumatic brain injury that radically changed Otis’ personality, and left him incapable of taking care of himself.

Otis was placed in Andover and other towns in a process called “boarding out,” where relatives of a person declared non compos mentis (of unsound mind) would pay for them to be housed and cared for by someone else. This was usually done by wealthier people who could afford the price tag, whereas poorer folks would often rely more heavily on their communities for support.

Otis stayed in Andover with Isaac and Jacob Osgood for four years, from about June 15, 1779 through to his death on May 23, 1783.1 This seems to be the longest Otis lived anywhere after being declared non compos mentis in 1771. But, why did Otis remain in Andover for so long? What set this town apart from Boston, Hull, and Barnstable?

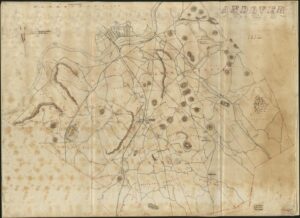

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

The People Make the Place

Andover sits about 20 miles from Boston, and by 1765 had 2,442 residents.2 Many of these folks shared a common last name: Osgood. John Osgood was one of the first settlers of the area, and his family grew into cornerstones of the community, serving as representatives to the General Court, soldiers, physicians, and church leadership. The well-established, successful Osgood family may have drawn Otis to the town, ensuring the maintenance of his comfort and social status.

And, of course, it helps to share politics. Most of the Osgoods were fierce patriots. Otis’ host, Captain Isaac Osgood, not only served in the French and Indian War, but was also one of nearly 330 Andoverians that marched to Lexington on April 19, 1775 (they arrived after the fighting had ended, but it’s the thought that counts). Two of Isaac’s sons, Jacob and Rev. David Osgood, served in the Revolutionary War, as did relative Dr. Joseph Osgood, among others. Even more Osgoods were patriot politicians and served as government leaders in the newly established commonwealth.3

As a well-known (and outspoken) patriot in a vulnerable position, Otis needed allies who could simultaneously support his politics by keeping him updated about the war, and provide him peace through a calm, rural residence. The Osgoods offered him just this.

We do not know exactly how the Otises and Osgoods met, or precisely what prompted Samuel Allyne to board his brother with them. We do know though, that the families were intertwined after Otis’ arrival: In 1782, Otis’ niece Elizabeth married Dr. George Osgood, son of Dr. Joseph Osgood.4 There is no record of how these two met, but it is not impossible to think that Elizabeth met George on a trip to see her uncle.

“Prepared to Receive Insane Patients”

Eighteenth century Andover had a reputation for providing medical care for those with mental illnesses. Otis himself visited Andover for this exact care in December 1778, while he was still living in Barnstable. Otis was seen by Dr. Daniel How, a physician famous for treating mental illness. Even the Massachusetts Provincial Congress knew of him, passing a resolution in 1775 that mentioned that Dr. How was “prepared to receive insane patients and is well skilled in such disorders.”5

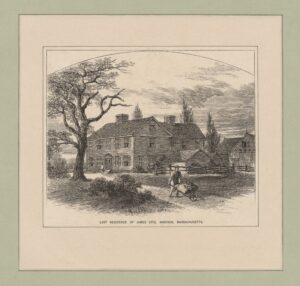

©Andover Center for History and Culture, Massachusetts

It is possible the Otises heard of Dr. How from members of the Provincial Congress, or maybe How’s reputation had already spread across Massachusetts. No records remain to indicate if Otis’ 1778 visit improved his mental state, but just six months later, Otis moved up to Andover. Dr. How’s presence could have been a motivation to move there.

Dr. How was not the only physician in town who treated mental illness. Dr. Thomas Kittredge was also famous for taking on patients with mental disorders, apparently treating up to twelve at a time. Dr. Kittredge also arranged for his patients to board with a handful of Andover families during their treatments, but whether or not the Osgoods were one of these families is unknown.6 Otis is not recorded as seeing Dr. Kittredge while boarding in Andover, but the fact that both Doctors Kittredge and How chose to practice in Andover could be indicative of a society more accepting of and caring for those with mental illnesses.

Rest and Relaxation

One last reason Otis was boarded in Andover might have less to do with what Andover was and more to do with what it was not: Boston. Otis probably had both positive and negative associations with his bustling homebase. It was the site of some of his greatest political triumphs, but also the stage for his public fall from glory and private turmoil. The rural setting of Andover offered peace, structure, and respite from his familial and political troubles.

From the New York Public Library

By the time Otis was caned by John Robinson in 1769, he had already suffered for years from the stress of Boston’s politics, complaining to his sister Mercy Otis Warren in 1766 of his weariness and anxiety.7 It did not help that his wife, Ruth Otis Cunningham, was a fierce loyalist. Otis’ avoided family confrontation by abusing alcohol, and local townspeople saw him in a drunken stupor more than once in the late 1760s.8 After his brain injury, Otis’ behavior only got worse, and his mental decline became more public.

In May of 1770, Otis’ physicians ordered him to the countryside in hopes it would improve his condition. While he improved enough to return home, by December 1771, he was officially declared non compos mentis and brought out of Boston, this time “carried off […] in a postchaise bound hand & foot.”9 Otis spent the rest of his life living away from his family and Boston for years at a time. While we cannot know for certain that being away from the town helped his mental state, we do know that when Otis returned to Boston, it was not long before he was returned to the countryside.10

While in Andover, the Osgoods allowed Otis to tutor their children in classical languages (a subject Otis loved) and help around their large farm, which gave him purpose and routine.11 In the eighteenth century, it was common to engage those with mental illnesses (both in private boarding situations and government institutions) in structured, simple manual labor.12 The thought was that structure and purpose would help them return to their “normal” state.

Before Otis’ death in 1783, he allegedly told his host, “Osgood, if I die while I am at your house, I charge you to have me buried under those trees […] You know my grave would overlook all your fields, and I could have an eye upon the boys and see if they minded their work.”13 Whatever he had been doing in Andover, he seemed to find enough peace that it was worth resting there forever.

Lucy Pollock photo

Buried in Boston

Sadly, Otis’ burial wish was not granted. He died in Andover after being struck by lightning on May 23, 1783, and within days his body was brought back to Boston. He was buried in the Cunningham family plot in Granary Burial Ground, where he lies today near the graves of his patriot friends and loyalist wife.

Especially during the summer, modern Granary is hectic. Clumps of tourists move slowly, yet aggressively, congesting the narrow paths to see Otis and others—loudly rehashing the dramatic story of revolutionary Boston. While Otis’ proximity to other historical figures like John Hancock and Paul Revere certainly helps cement him into the revolutionary story, we might wonder if the peaceful, nearly abandoned Osgood family plot in Andover might have given him a more fitting resting place.

- Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, probate & family court records, Probate and Family Court Department FILE PAPERS, Box 083 Cases 16131-16390, 1636-1894, Family Search, Case number 16253, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS2L-RSZP-B?cat=2822393&i=1052&lang=en

- “Andover – Population,” Andover Answers from Memorial Hall Library, accessed August 22, 2025, https://answers.mhl.org/Andover_-_Population and “116 Osgood Street,” Andover Historic Preservation, accessed August 15, 2025, https://preservation.mhl.org/116-osgood-street

- Abiel Abbot, History of Andover, from its settlement to 1829 (Flagg and Gould, 1829), 57–58, and Kathleen Osgood and Richard Pitra, “The Osgoods: 250 Years Ago They Started a Revolution,” NorthAndoverCAM, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDzqEfJaZdA

- “Elizabeth (Otis) Osgood (1760-1802),” WikiTree, accessed June 11, 2025, https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Otis-982

- Sarah Loring Bailey, Historical sketches of Andover, comprising the present towns of North Andover and Andover (Houghton, 1880), 331, https://www.loc.gov/item/01011213/

- Albert Deutsch, The Mentally Ill in America: A History of their Care and Treatment from Colonial Times (Cambridge University Press,1949), 21, https://archive.org/details/mentallyilliname00deut

- James Otis to Mercy Otis Warren, 11 April 1766, in Warren-Adams Letters Being Chiefly a Correspondence Among John Adams, Samuel Adams, and James Warren, vol. 1, 1743-1777 (Massachusetts Historical Society, 1917), 1-2.

- Holland, Gerald, “Lightning Bolt of Liberty: The Legacy of James Otis and His Role as a Pre-Revolutionist,” Liberty University (2025): 118.

- “To Sir Francis Bernard,” in The Correspondence of Thomas Hutchinson, Volume 4: November 1770-June 1772, Colonial Society of Massachusetts, https://www.colonialsociety.org/node/4782#chsect922

- Bailey, Historical Sketches of Andover, 389-390