“You Think This is a Massacre? Just Wait!”: The Anti-Busing Movement’s Use of Revolutionary Boston History

Written by Lou Rocco, Director of Museum Operations & Experience

In the wake of a monumental 1974 court decision which ordered Boston to address racial segregation in its public schools through busing, opponents resisted the decision in a variety of ways. This included invoking the memory of two of Revolutionary Boston’s most significant events: the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party.

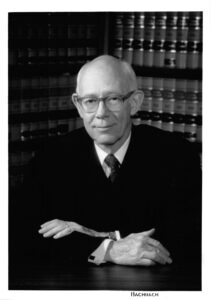

Robert Bachrach, Photographer, courtesy of the United States District Court

Morgan v. Hennigan

On March 15, 1972, the Boston chapter of the NAACP filed a lawsuit in federal court against the Boston School Committee (BSC) on behalf of dozens of Black parents and school children. The NAACP claimed that the BSC engaged in discriminatory practices and policies which segregated the city’s white and Black students, and directed more funding and resources to majority-white schools than majority-Black schools. This lawsuit, known as Morgan v. Hennigan, was named after parent Tallulah Morgan and BSC Chairman James Hennigan.

On June 21, 1974, Federal District Judge Wendell Arthur Garrity Jr. issued his opinion in Morgan v. Hennigan. In his opinion, Garrity found that the BSC had, “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation affecting all of the city’s students, teachers and school facilities and have intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system. Therefore the entire school system of Boston is unconstitutionally segregated.”1

To remedy this constitutional violation, Judge Garrity ordered the BSC to adopt a desegregation plan written by the State Board of Education after the BSC consistently refused to write one that adequately addressed racial imbalance in the city’s schools. The state’s plan, known as Phase I, required students to be bused to schools outside of their neighborhoods in order to achieve racial balance across the city and went into effect on September 12, 1974. Phase I lasted throughout the 1974–1975 school year.

Anti-Busing Resistance

Courtesy of Connor Anderson via Flickr

Judge Garrity’s order was met with considerable resistance from certain white, working-class neighborhoods and communities in Boston. Those who opposed busing and desegregation formed multiple organizations, key among them being Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR), led by Louise Day Hicks, a prominent lawyer and elected official from South Boston. The resistance movement adopted many of the tactics and strategies used by the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s, including wearing buttons and chanting at rallies and marches, boycotting public schools and founding alternative schools, holding prayer vigils, defacing buildings with graffiti, and conducting sit-ins and sleep-ins.2

At the same time, the anti-busing movement sought to contrast itself with radical anti-war and civil rights advocates by wrapping itself in the American flag, deliberately adopting and displaying patriotic symbols.3 This effort included appropriating the memory and spirit of two of Revolutionary Boston’s most famous events.

ROAR Takes the Boston Massacre

The first Revolutionary-era event anti-busing demonstrators sought to co-opt was the Boston Massacre. On March 5, 1975, the 205th anniversary of the Boston Massacre, ROAR gathered for its regular weekly meeting in the City Council chamber inside City Hall. This meeting space was a privilege afforded to ROAR by virtue of Hicks’ membership in both ROAR and the Boston City Council.

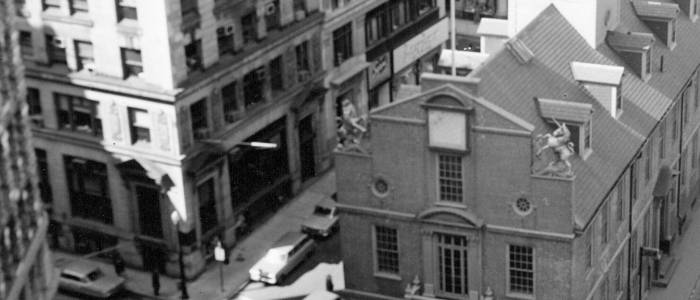

Old State House, ca. 1962-1969

Melvin J. Gillette

VW0008.002035

Collection of Revolutionary Spaces – Bostonian Society

After the meeting adjourned, around 400 ROAR members exited onto Congress Street and began a mock funeral procession to the Old State House, the site of the Boston Massacre. Two drummers led the march, which included several pallbearers carrying a coffin containing a woman playing the corpse of “Miss Liberty.” On the side of the coffin was inscribed the words, “R.I.P. Liberty—Born 1770-Died 1974.” Marchers also carried anti-busing signs with Revolutionary-tinged slogans including, “We Have Just Begun To Fight! Resist The Tyrant King Garrity!,” “Beware The Minutemen Await The Signal – One If By Land, Two If By Sea To Stop Forced Busing,” “We Have Not Yet Fired The Shot Heard Round The World! Don’t Push Us,” and “You Think This is a Massacre? Just Wait!”4

When the procession stopped at a reviewing stand near the Old State House, ROAR members sang and chanted while they awaited the beginning of the annual Boston Massacre reenactment. While the ROAR crowd parted to allow the reenactors to access the space in front of Old State, they disrupted the program to the point where the narrator of the reenactment had to ask them to stop. The reenactment then continued as planned, and when it reached its expected climax and the soldiers fired their muskets into the crowd of colonial Bostonians, something unexpected happened: all 400 ROAR demonstrators fell down and played dead in an act of symbolic protest and historical appropriation.5

The “GarriTea” Party

Just over four months after ROAR’s demonstration at the Boston Massacre reenactment, a different anti-busing organization held its own Boston Tea Party. On July 12, 1975, around 70 members of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty boarded a replica of the Beaver, a ship involved in the Boston Tea Party, docked near Griffin’s Wharf, the site of the Boston Tea Party. But instead of throwing East India Company tea into Boston Harbor, protesters tossed school assignment slips and explanatory booklets for Phase II of the busing plan (written by Judge Garrity) into the water. Some even donned feathers on their heads in a nod to the crude Mohawk disguises worn by some of the original Tea Party participants in 1773.

State Representative Ray Flynn of South Boston declared at the event, “Just like they did 200 years ago, we want to show our opposition to an unjust tyrant,” in this case, Judge Garrity. Flynn and several others in attendance then filled a box labeled “GarriTEA” with the assignment slips and booklets, which Flynn then dumped overboard into the harbor while Hicks and anti-busing firebrand Elvira “Pixie” Palladino watched.6

(Ab)using the Revolution?

The anti-busing movement would not stage another demonstration that so dramatically or explicitly referenced Boston’s Revolutionary history following the “GarriTEA” Party in July 1975. Yet, protests, demonstrations, and resistance to desegregation and busing would continue in earnest until late 1977 when opponents begrudgingly resigned themselves to the reality of Judge Garrity’s order (which remained in effect until the late 1980s).7

The anti-busing movement’s use of Boston’s Revolutionary history may have reflected a shrewd political calculation on the part of some movement leaders. Perhaps they believed that connecting their movement to the legacy and lineage of the American Revolution in the eyes of the public would imbue their cause with enough political legitimacy and strength to overwhelm and reverse Judge Garrity’s order. At the same time, it may have reflected a genuine belief among ordinary Bostonians who opposed busing that they and their cause were legitimate heirs of Boston’s Revolutionary generation. It is likely that both of these motivations were present, as the anti-busing movement was not a monolith and contained a range of perspectives, arguments, and beliefs.

Regardless as to their motives, the anti-busing movement’s attempt to co-opt the memory and meaning of the Boston Massacre and Boston Tea Party speaks to the enduring influence of those Revolutionary events in the hearts and minds of Bostonians more than 200 years after their happening. It also raises important questions which Americans continue to grapple with today: Who does this history belong to? What do we owe past generations of Americans when we use their lives and stories in the name of contemporary political causes? When, if ever, is it appropriate to invoke the memory and legacy of the American Revolution for political ends? And what does using this history in a political context do to our collective respect for and interest in it?

To learn more, visit Revolutionary Spaces’s exhibit An Unfulfilled Promise: Desegregation and Busing in Boston, on display now for a limited time at the Old State House.

1 Morgan v. Hennigan, 379 F. Supp. 410 (D. Mass. 1974), Justia, accessed August 23, 2024, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/379/410/1378130/.

2 Ronald P. Formisano, Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 139-140.

3 Formisano, Boston Against Busing, 150–151.

4 James Ayers, “Boston Foes Take Their Protest to Replay of Boston Massacre,” Boston Globe, March 6, 1975, page 6; J. Anthony Lukas, “Who Owns 1776? The Battle in Boston for Control of the American Past,” New York Times, May 18, 1975, pages 39–40.

5 Lukas, “Who Owns 1776?,” pages 39–40.

6 “Boston Busing Foes Dump ‘GarriTEA’ into Harbor,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1975, page 10.

7 “Busing, Segregation, and Education Reform in Boston,” Poverty USA, https://www.povertyusa.org/stories/busing-segregation-and-education-reform-boston, accessed August 26, 2024; “Desegregation Busing,” Boston Research Center, Encyclopedia of Boston, https://bostonresearchcenter.org/projects_files/eob/single-entry-busing.html, accessed August 26, 2024.; Formisano, Boston Against Busing, 195–196, 213.