America’s Bicentennial

By Sara Dean, MA in Public History student at Northeastern University

The Legacy of Crispus Attucks – Part IV

This post is part of a series exploring the legacy of Crispus Attucks, the first victim of the Boston Massacre. These posts were written by students in the Master of Public History program at Northeastern University. Crispus Attucks was an enslaved man of African and Native American heritage about whom little is known, but his legacy has been important to successive generations of Americans. For more information about the life and legacy of Crispus Attucks, see First Martyr of Liberty: Crispus Attucks in American Memory by Mitch Kachun (Oxford University Press, 2017).

“And honor to Crispus Attucks, who was leader and voice that day;

The first to defy, and the first to die, with Maverick, Carr and Gray.

Call it riot or revolution, his hand first clenched at the crown;

His feet were first in perilous place to pull the king’s flag down;

His breast was the first one rent apart that liberty’s stream might flow;

For our freedom now and forever, his head was the first laid low.

— From “Crispus Attucks” by John Boyle O’Reilly, 1888.

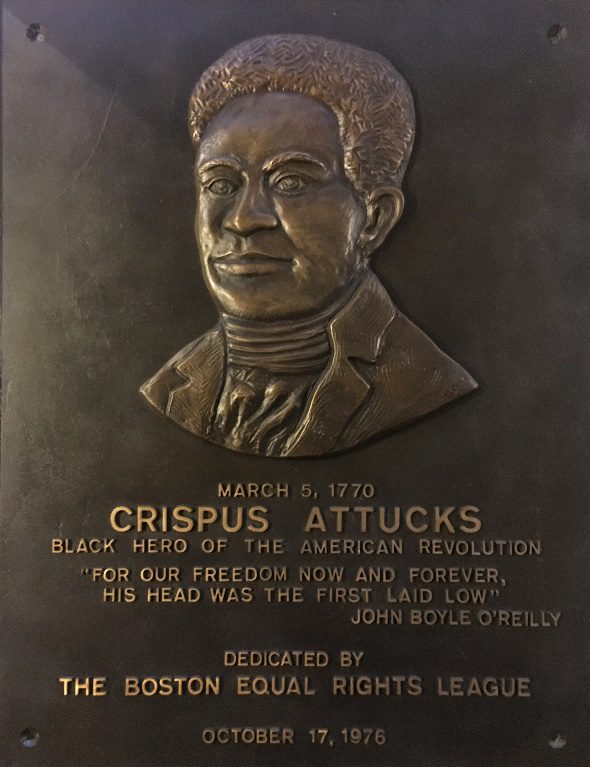

On October 17, 1976, to mark the bicentennial, the Boston Equal Rights League and the City of Boston held a ceremony in honor of Crispus Attucks, whom many considered an African American patriot and the first martyr of the American Revolution. The event began with a parade which proceeded past the Old Granary Burying Ground, where Attucks lies buried with the other victims of the Massacre, to Faneuil Hall. An estimated 450 people heard remarks by Edward W. Brooke, the first African American to be popularly elected to the United States Senate, and William Owens, Massachusetts’ first African American state senator. Clarence “Jeep” Jones, the first African American Deputy Mayor of Boston, presided over the ceremony. At the Old State House, The Equal Rights League dedicated a commemorative plaque to honor Crispus Attucks, which the Bostonian Society has in its collection today.

The plaque reads:

March 5, 1770

Crispus Attucks

Black Hero of the American Revolution

“For our freedom now and forever,

his head was the first laid low.”

John Boyle O’Reilly

Dedicated by

The Boston Equal Rights League

October 17, 1976

The year 1976 marked the two-hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the Declaration of Independence and the height of the bicentennial era. For marginalized peoples, especially African Americans, this was a fraught and confusing time. Some people questioned why African Americans should support the bicentennial at all, given the civil rights abuses they continued to suffer. By the mid-1970s, the city of Boston was still in the throes of conflict over racial desegregation with its implementation of busing desegregation from 1974 to 1988, which involved the transportation and exchange of students between black and white public schools. During the bicentennial period, white antibusing demonstrations tapped into public memory of the American Revolution both intentionally and unintentionally. In 1975, four hundred ROAR (Restore Our Alienated Rights) protestors picketed a Boston Massacre reenactment and dramatically fell to the ground when British soldier reenactors fired their guns. The following year, antibusing demonstrators infamously invited another comparison to the Boston Massacre when they attacked African American lawyer Ted Landsmark. In a June 1976 editorial entitled “The Bicentennial Blues,” Ebony writers marveled that this had taken place “within sight and sound of Faneuil Hall,” near the site where Attucks had died. When Senator Brooke gave his 1976 Attucks Day address at Faneuil Hall, he rightly observed: “Here and now in this room, you and I are still fighting for freedom…more than 200 years later.” Brooke condemned the “white and black, separate and unequal” split in American society and American schools, and Senator Owens affirmed Attucks’ reputation as a martyr who “gave his life” for all the people of Boston.

The Equal Rights League commemorative plaque features an excerpt from the poem, “Crispus Attucks,” by Irish American poet and civil rights activist John Boyle O’Reilly. O’Reilly wrote the poem in 1887 or 1888 after the Massachusetts General Court announced its decision to erect a monument to the Boston Massacre in Boston Common. At the dedication ceremony for the monument, which also came to be known as the “Attucks Memorial,” a clergyman from New Bedford, MA, read O’Reilly’s poem aloud in Faneuil Hall. Although O’Reilly’s poem predated Boston’s desegregation crisis by nearly a century, and is older still today, it remains painfully relevant. Frustrated by the shortcomings of American freedom, O’Reilly wonders:

“And now, is the tree to blossom? Is the bowl of agony filled?

Shall the price be paid and the honor said and the word of outrage stilled?

And we who have toiled for freedom’s law, have we sought for freedom’s soul?

Have we learned at last that human right is not a part, but the whole?

That nothing is told while the clinging sin remains part unconfessed?

That the health of the nation is periled if one man be oppressed?

— From “Crispus Attucks” by John Boyle O’Reilly, 1888.

Boston (Mass.) City Council. A Memorial of Crispus Attucks, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, Samuel Gray, and Patrick Carr: From the City of Boston. Printed by Order of the City Council, Boston, 1889.

Hawes, Alexander, Jr. “Ceremonies Honor Black Killed in Boston Massacre.” Boston Globe (1860-1986). Boston, MA. October 18, 1976:5.